Content from Introduction

Last updated on 2022-11-15 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 40 minutes

How Websites Work

Overview

Questions

- What is static web content?

- Why should I use GitHub or GitLab Pages to create my website?

Objectives

- Explain what a static site generator does.

- Choose the appropriate tool for a website/project.

When we use a web browser to visit a page on the World-Wide Web, the browser asks for information from a server - a computer storing the data relevant to the site and configured to receive and respond to requests for that data. Assuming there were no problems at this stage (e.g. asking for a page which doesn’t exist, or being unable to reach the server), our browser receives and interprets this information to render and display the webpage on our screen. (A web developer would probably be horrified to read such a gross oversimplification, which is just one reason why web developers are not the target audience of this tutorial.)

The page displayed by the web browser is the result of combining HTML - a hierarchical format describing the structural elements of the page and their raw content - with CSS - an ordered set of styling instructions telling the browser how the content should be organised and formatted - and any images that should be embedded in the page. Other information received from the server, but not displayed by the browser, includes metadata, cookies, and other non-visible elements in the HTML - information about the site that could be relevant for a computer but probably isn’t interesting to a human (there are exceptions to this) - and scripts that the browser may run to do something in response to various triggers.

Hello World in HTML

When learning a new programming language, you may often find a

reference to the popular Hello world example. These

examples typically capture the simplest code that can produce and

display the text “Hello, World!” on screen.

As HTML requires certain tags to be present and almost always in

matching pairs (open <tag> and closing

</tag>), HTML documents tend to get verbose rather

quickly.

The simplest, valid HTML Hello world is:

HTML

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Page title</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>Hello, World!</p>

</body>

</html>So as you can imagine, writing long HTML documents by hand is rather painful. Notice that we didn’t specify anything about how and where the text should be displayed.

To achieve this we would additionally need to include stylized tags or Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) instructions. If you do not provide CSS instructions (either inside your HTML document or as a separate file), a web browser will make a best guess regarding the layout of HTML elements on the page based on its defaults.

Exercise: Writing Basic HTML

Given the stylized text:

Hello, World!

write the HTML that will produce the same result. Hint the big font is achieved by use of a heading.

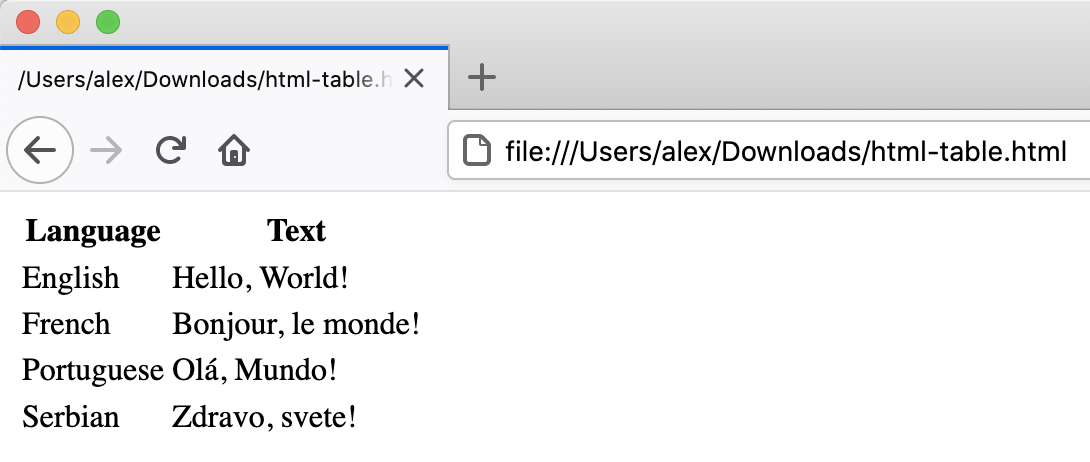

Let’s write a more complex HTML example using a table showing the

“Hello, World!” text in different languages that renders like:

The HTML to produce such a table looks like this (you can copy+paste the snippet into the HTML file you created in the previous example):

HTML

<table>

<tr><th>Language</th><th>Text</th></tr>

<tr><td>English</td><td>Hello, World!</td></tr>

<tr><td>French</td><td>Bonjour, le monde!</td></tr>

<tr><td>Portuguese</td><td>Olá, Mundo!</td></tr>

<tr><td>Serbian</td><td>Zdravo, svete!</td></tr>

</table>Each row is enclosed between table

row <tr> and

</tr> tags. Within a row, <th> and

</th> tags are used to contain table

headings (special table cells displayed in bold font),

while regular table data cells are

contained within <td> and </td>

tags.

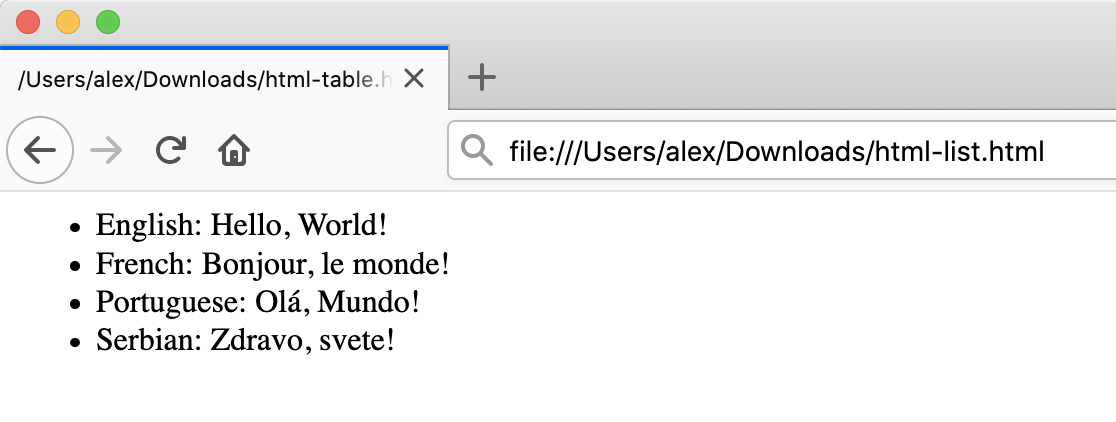

A similar example written using HTML lists would look as follows:

HTML

<ul>

<li>English: Hello, World!</li>

<li>French: Bonjour, le monde!</li>

<li>Portuguese: Olá, Mundo!</li>

<li>Serbian: Zdravo, svete!</li>

</ul>Here, we used unordered list tags

<ul> and </ul> to define a list

with 4 items, each in turn wrapped in individual list

item (<li> and

</li>) tags.

Static vs Dynamic Sites

Static pages are those whose contents are stored on a server in a state ready to be sent to any user who makes a request for that web page. When a request is made, the server only needs to send the information comprising that web page (such as HTML and CSS). Sites that do not change often, such as a website containing one’s CV, are often stored as static sites.

Conversely, dynamic sites are those that have their pages generated when a user makes a request for a web page. Depending on when the request is made, the content might change; for example, clicking refresh when viewing a discussion in a web forum might result in new comments showing up. The key difference is that static pages need only be generated once, after which they rest unchanged on the server, compared to dynamic pages which are regenerated by a server every time it receives a request. This lesson focuses on static sites and tools that can be used to create them, known as Static Site Generators.

One of the advantages of using static site generators is that they remove the need for us to manually produce a lot of HTML, allowing us to focus on the human-readable content we want our pages to contain. However, we still need a way to tell the generator how we want our content to look when it’s displayed in the browser. For that, we will use a tool called Markdown, which we’ll learn about in the next episode.

Figure 1.1: Page Generation Alternatives. This figure is a modified version of the original published in [JavaScript for Data Science][js4ds], and is reproduced here with permission from the author.

Static-generated sites are a great choice when the information you want to display on a website is the same regardless of who visits your site and when, and if the content of your pages is unlikely to need to change very often. This makes Static Site Generators a good choice for sites that provide documentation or lesson content like this page: the aim of the page is to deliver the same information to every visitor. The visitor can arrive, (hopefully) find and read what they need, and leave feeling happy and fulfilled.

Dynamic sites provide a lot more possibilities for providing interactivity and personalised or topical content. But creating them is a degree more complicated and also places considerable additional burden on the server, not least in terms of computational requirements and security considerations. Among other things this means that, unlike with static pages (see the rest of this lesson), you’re unlikely to find cost-free platforms to help you deliver dynamic content.

Exercise: The Perfect Tool for the Job

Given the following types of websites, reason if a static site generator is an appropriate solution to implement them.

- A personal website with About and Projects sections

- A forum or discussion platform

- A community blog or news website

- A search engine (such as google.com)

- A wiki (such as wikipedia.com)

- An online book

- personal website: In most cases, Yes. This kind of content is typically written/edited by one person and meant to have a read-only access to visitors.

- forum or discussion: Most likely No. Such website requires interactivity and ways to identify who wrote what content.

For questions 3 and 5 the answer is both Yes and No depending on the requirements and necessary functionality.

- blog/news: A simple blog or news website, maintained by a small set of users, is perfectly achievable by using a static generator. For very large groups of content creators or if access to articles needs to be controlled individually, using a static generator will lead to difficult technical challenges.

- search engine: Most often No. Implementing something as sophisticated as Google’s search would be close to impossible with a static generator. There are ways to have a simple engine that searches across all pages produced by a static generator using indexing and making clever use of browser features but this approach has many limitations.

- wiki: A simple wiki is perfectly doable with a static generator (e.g. GitHub Wiki Pages), however it becomes limiting as soon as its content needs to be edited or discussed by many users, as is the case of Wikipedia.

- online book: Definitely Yes. Static generators are perfect for this type of website. They typically provide ways to avoid repeating content (variables and templates), automatic creation of a Table Of Contents, among other goodies.

GitHub Pages

If the site you want to create is a good match to the strengths of a static site generator - it’s relatively small, will be updated relatively infrequently, and the content does not need to be personalised to the visitor - then creating it with GitHub Pages is a good option. GitHub Pages is a system allowing users to create and serve websites directly from their GitHub repositories. The service is free for public repositories and simple pages can be created and served with very little configuration required.

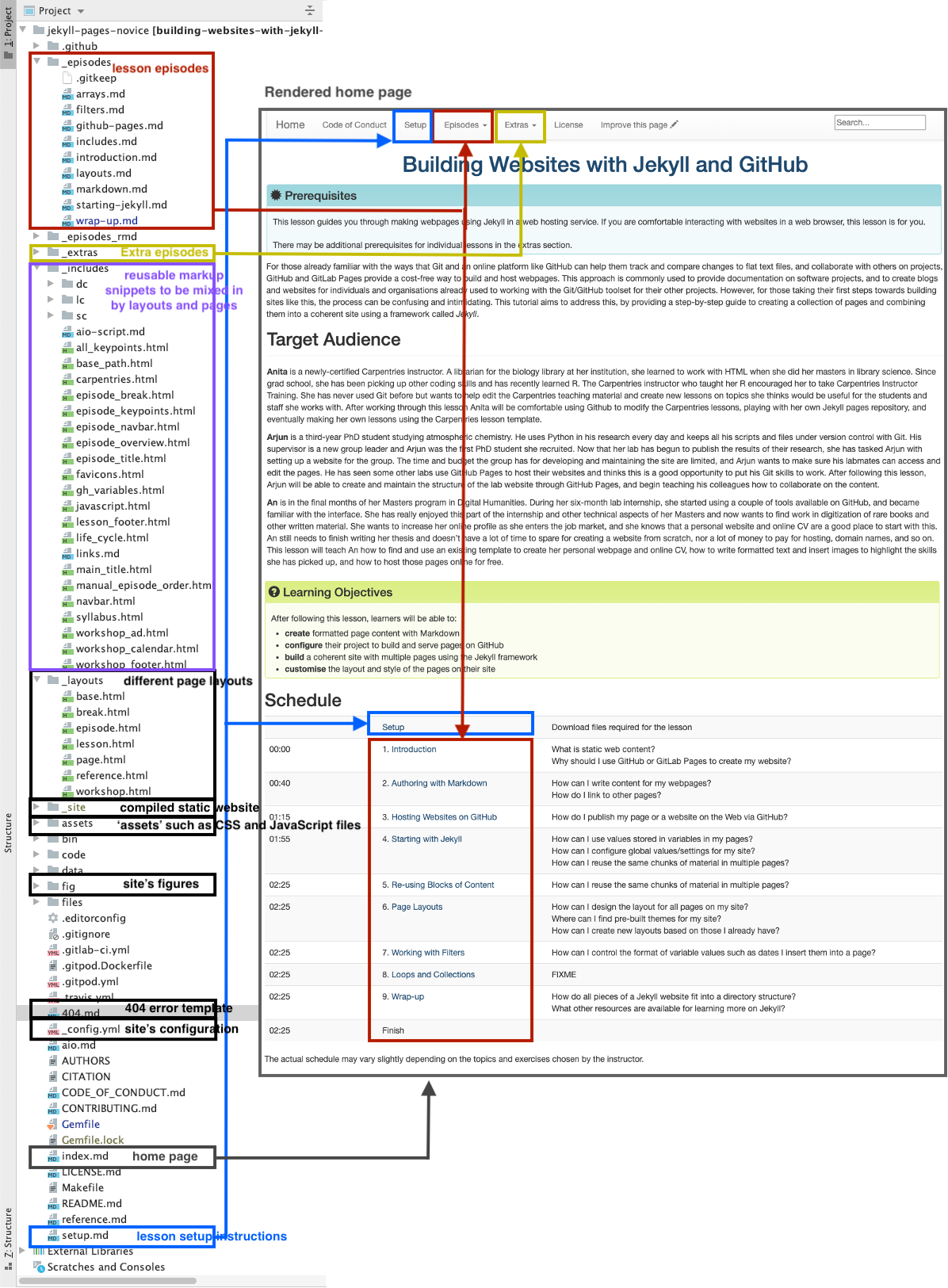

Behind the scenes GitHub Pages uses a static site generator called Jekyll, which we’re going to learn about later in this lesson. There are many different technologies that come together when creating a website with GitHub Pages that you have to be familiar with (as shown in the diagram below). It may sound overwhelming at first but we will explain most of these technologies in this lesson - we only don’t cover CSS/Sass (styling language that gets compiled into CSS) and JavaScript/CoffeeScript (scripting language that gets compiled into JavaScript) in detail.

First, we are going to set up a repository to store our files and learn more about how to author and format the content of our pages using HTML and Markdown, before configuring GitHub to display this content as a website using GitHub Pages.

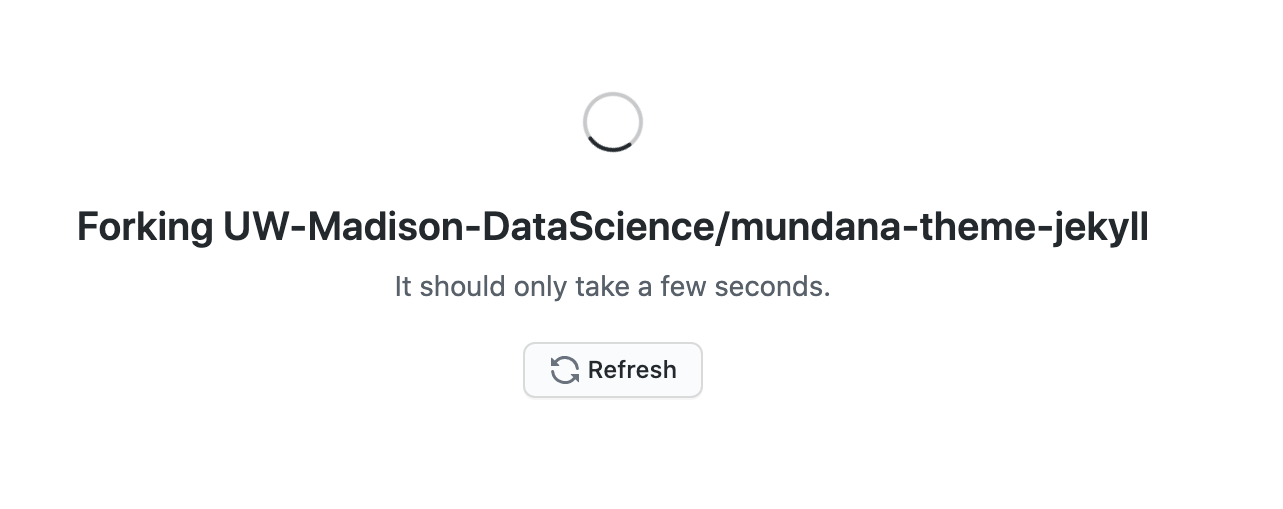

Setting Up a Repository

Before we get into working with Markdown we must first create a

repository to work in. This repo (short for repository) is similar to a

folder on your computer, the main differences being that the folder

lives on the web in GitHub/GitLab (though you can also keep a copy on

your computer if needed) and that folder is using a version control

software called [git][git] to track changes to the files.

For our purposes we will mostly be ignoring the version control

software, though it can be handy if you need to revert to old versions

(see [Software Carpentry - Version Control with Git][swc-git] for an

introduction). In this lesson we will be working with this folder on the

web to control the website we will be creating.

Setup a GitHub account

Before you can create a repo, you will need to create a GitHub account

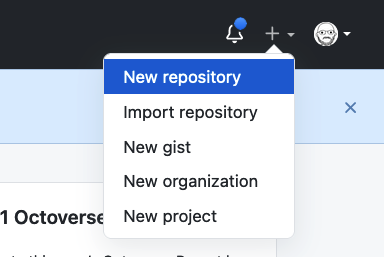

Make sure to login with your GitHub account and visit https://github.com. Click the green “New” repo button on the left hand side of GitHub:

or click the “+” menu in the upper righthand corner and choose “New Repository”.

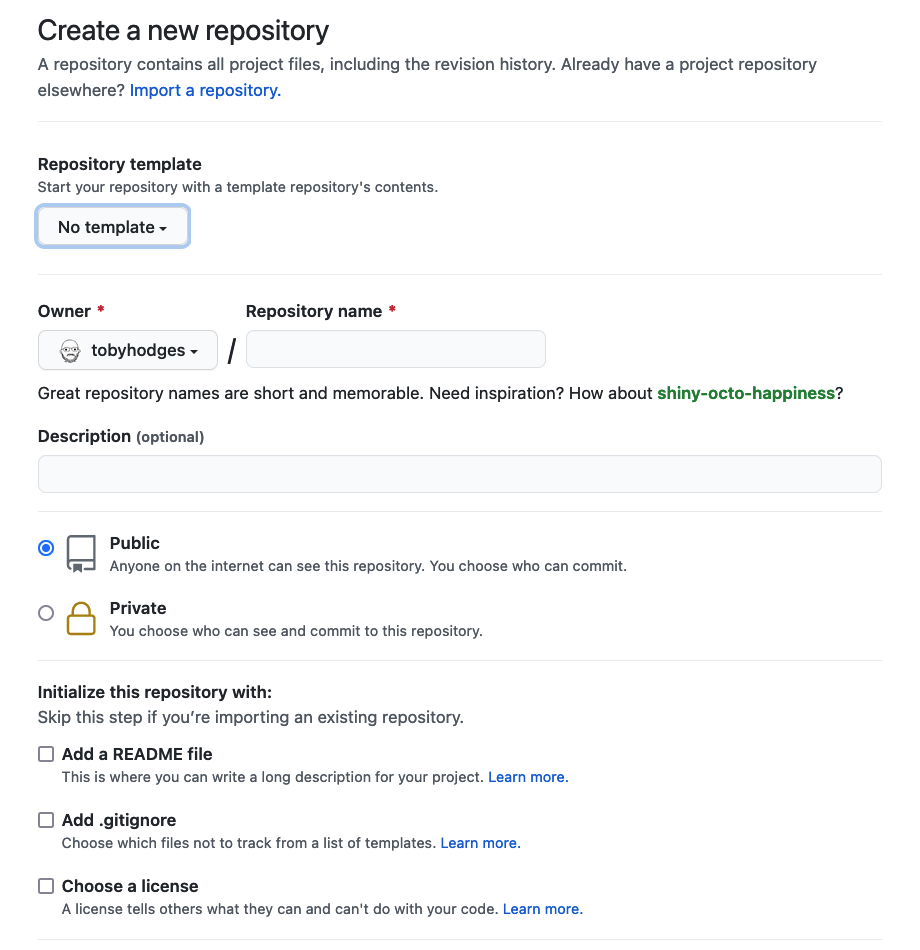

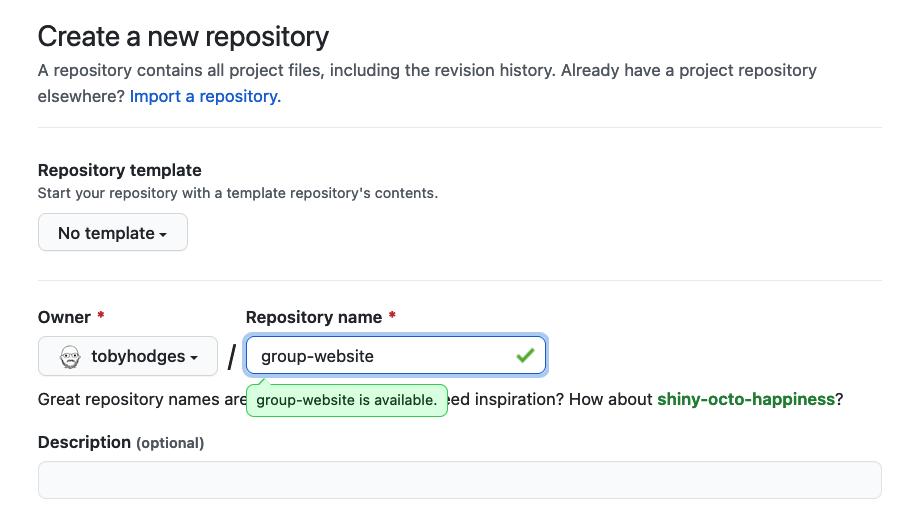

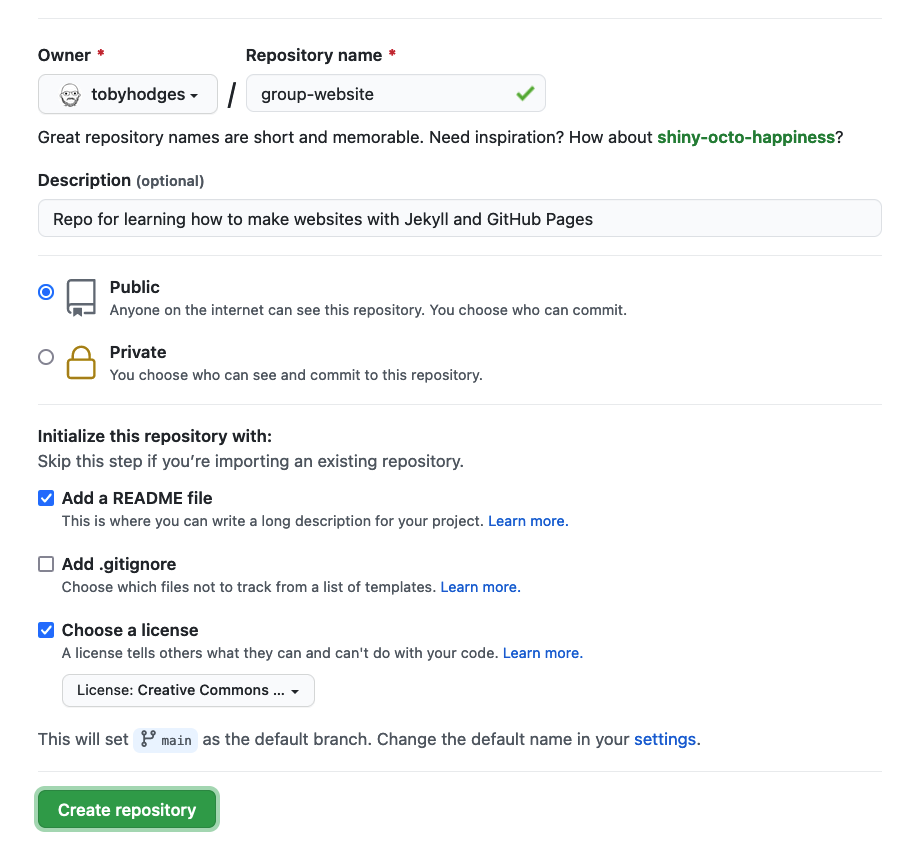

Next you will need to fill in some info about your repository.

In this lesson, we will be working on a general group website. You

can imagine this website may be for your lab group, a specific project

group, or another group you work with. Under the “Repository name” field

type group-website.

We can also add a description (for instance Repo for learning how to make websites with Jekyll and GitHub pages) so we know what this repo is when we find it again after the workshop.

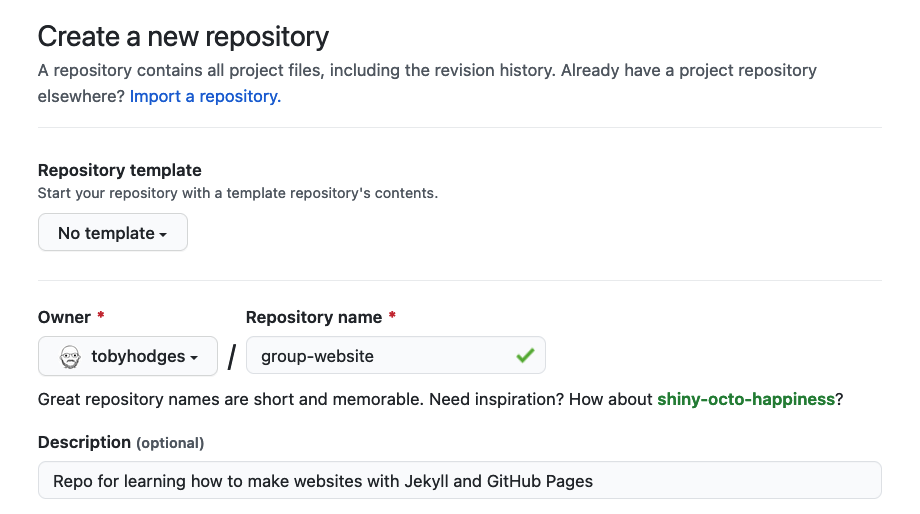

Under the “Initialize this repository with:” section we will check

Add a README file and Choose a license. It is

good practice to have a README file that gives more information about

your repo and to set a license for your work.

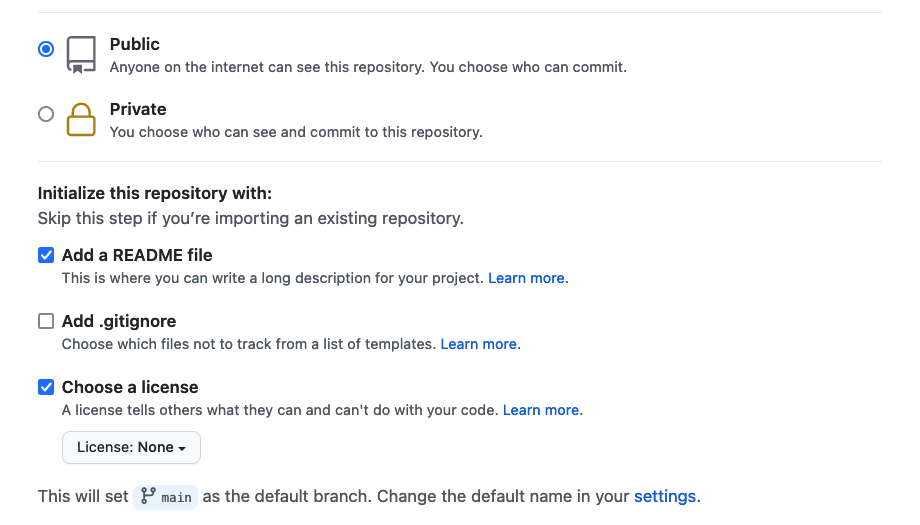

for this example repository we’ll use the

Creative Commons Zero v1.0 Universal (CC0) license, which

allows anyone to re-use and adapt the content of the repository without

restriction, but you may want to consider choosing something more

restrictive when you’re building your own website.

Checkout Other Licences

You may want to checkout this lesson or GitHub’s license documentation for more information about possible licenses.

Once you’ve finished these steps you can click the “Create Repository” button to finish creating the repo.

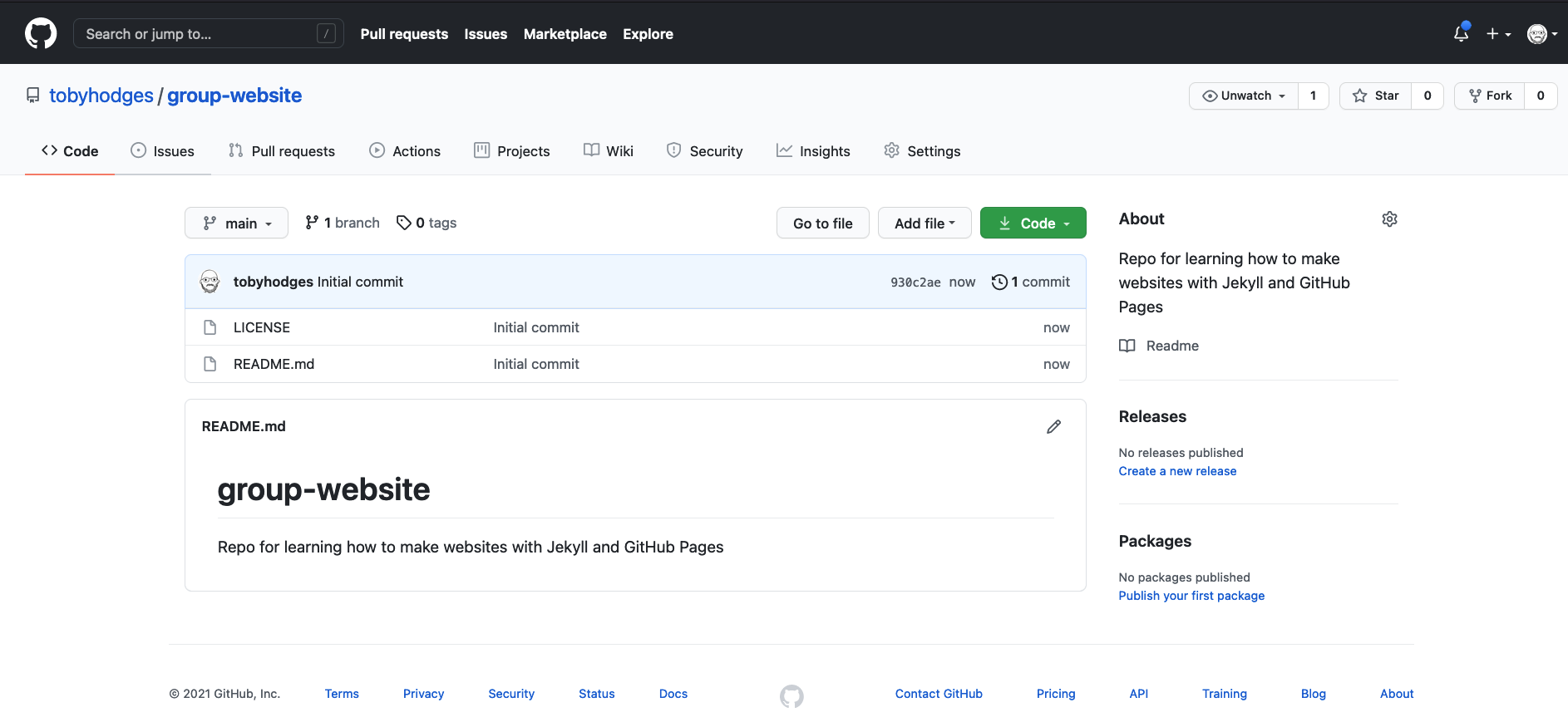

GitHub will then setup the repo and it should create the repo called

group-website with a README.md file and a

LICENSE file.

Key Points

- A static site generator combines page-specific content with layout elements and styling information to construct individual static webpages.

- GitHub Pages/GitLab Pages is a good choice for people who are already familiar with Git and GitHub/GitLab.

- This approach can be used to create a relatively small website/blog on a limited budget.

Content from Authoring With Markdown

Last updated on 2022-11-15 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 35 minutes

Markdown

Overview

Questions

- How can I write content for my webpages?

- How do I link to other pages?

Objectives

- Create simple pages with formatted text

Markdown is a language used to simplify writing HTML. Plain text

characters like # and * are used in place of HTML tags. These characters

are then processed by Jekyll (or another script or application) and

transformed into HTML tags. As the name Markdown suggests, the language

has been trimmed down to a minimum. The most frequently used

elements, like headings, paragraphs, lists, tables and basic text

formatting (i.e. bold, italic) are part of Markdown. Markdown’s

simplified syntax keeps content human-readable.

This is one reason it is a preferred language for formatted user input

on web sites like:

Where to Start Writing Markdown?

A lot of tools for rendering Markdown source code exist. Rendering is

the process of generating a nice view of the content using the style

information included in the source text. Chances are high, your editor

can do this. As we are working towards authoring websites using Jekyll

and GitHub pages, we will use GitHub straight away for learning the

basics of Markdown. The GitHub project you created in the last episode

contains a file README.md.

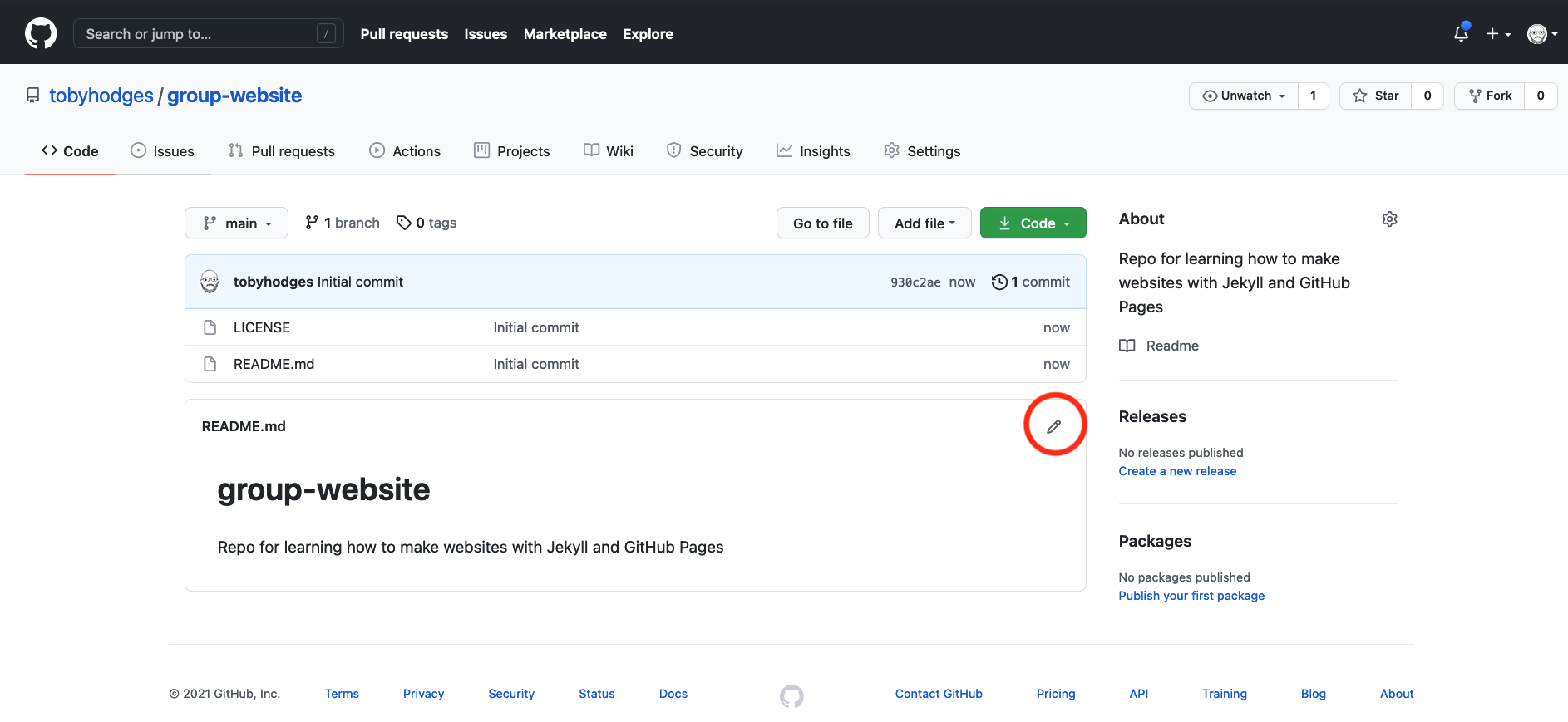

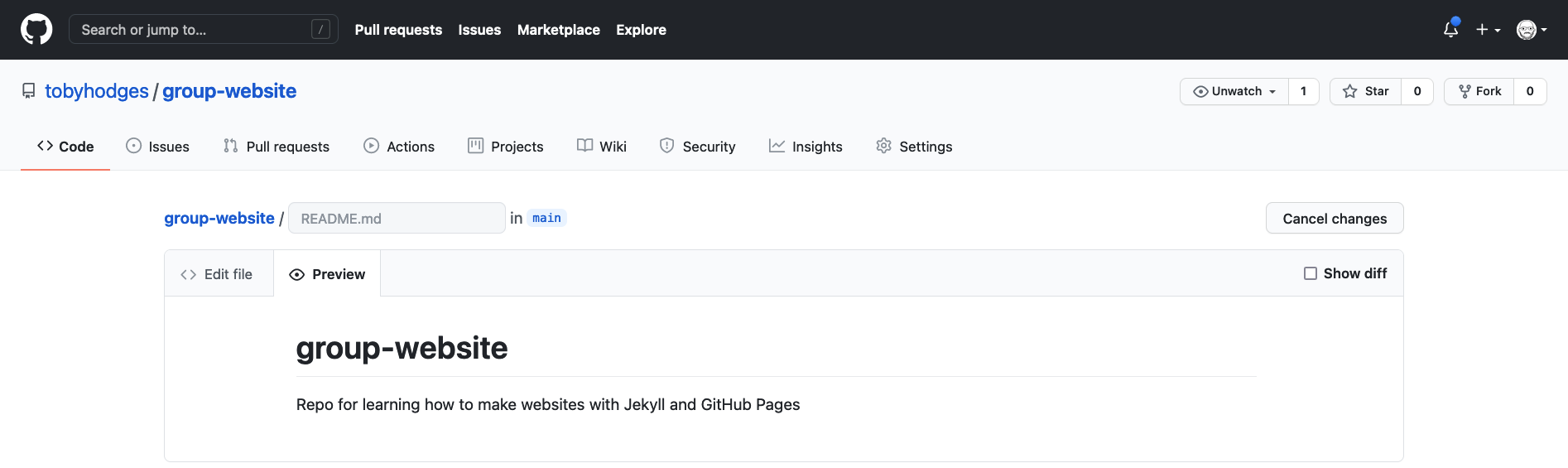

The image below shows the projects default view. This view includes a

rendered view of the content inside the file README.md.

Your project should look quite similar except for the red circle around

the pencil symbol.

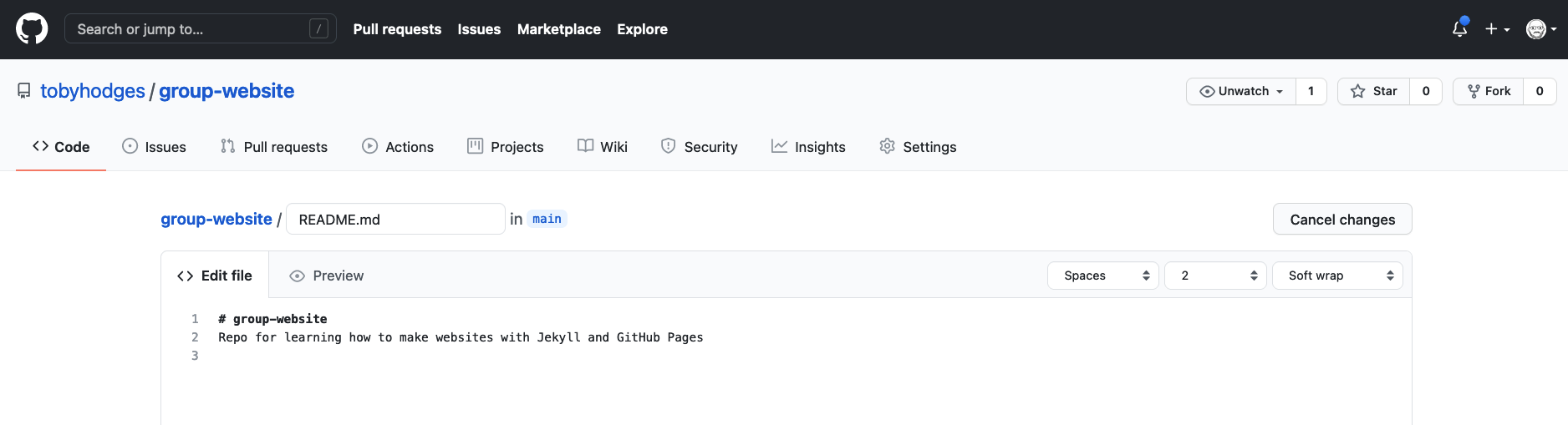

Click on that pencil symbol to open an editing interface of your

project’s README.md file. Once we’ve clicked the pencil

symbol, GitHub will open that file in the editing interface.

We can change the content and have a look at the rendered view by clicking the Preview changes tab.

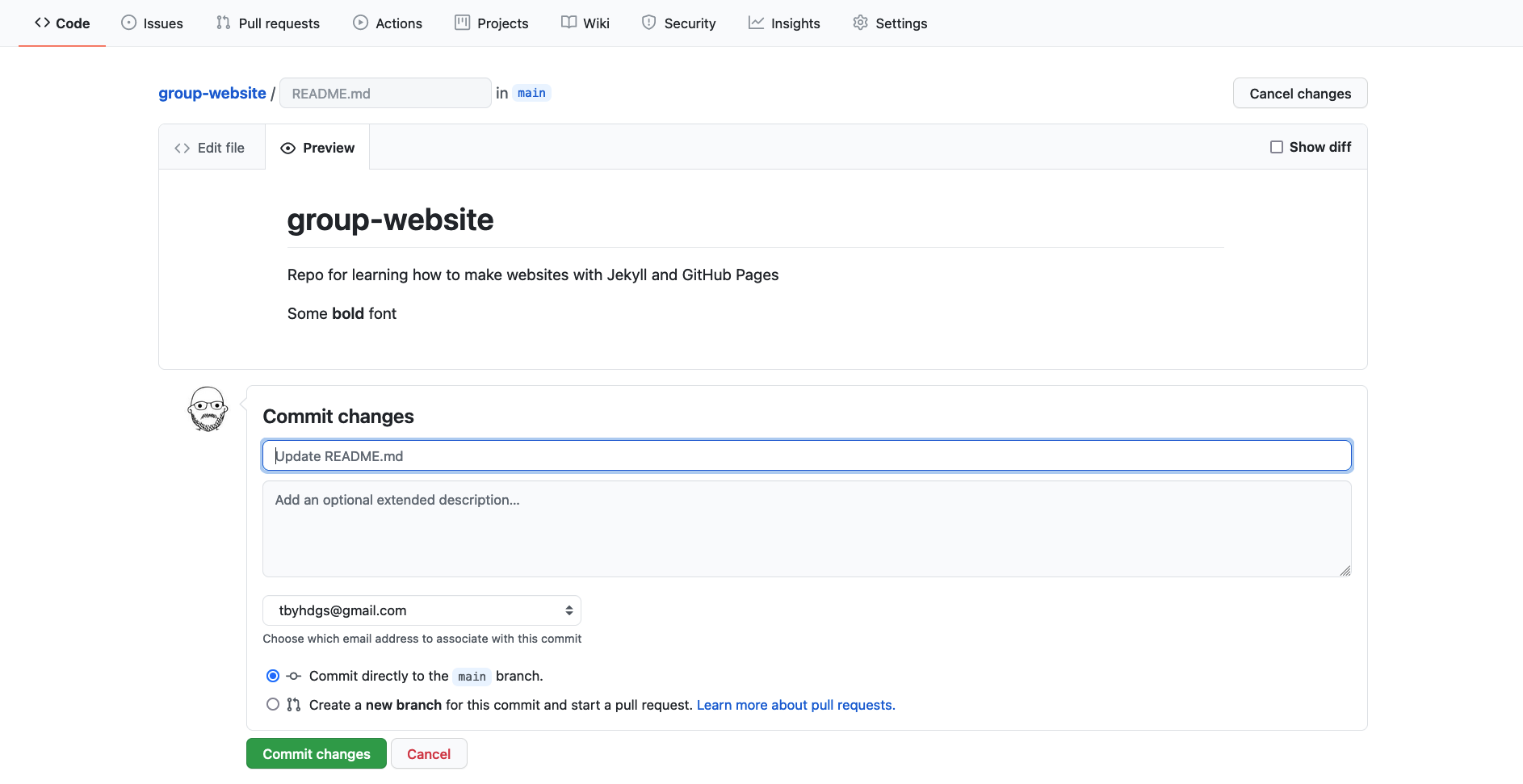

Let’s add Some **bold** font and see what happens when

we preview it using the preview tab. If you check the “Show diff” box on

the upper-right hand side, GitHub will show green vertical bars visually

highlighting the new content. To save the content to the file

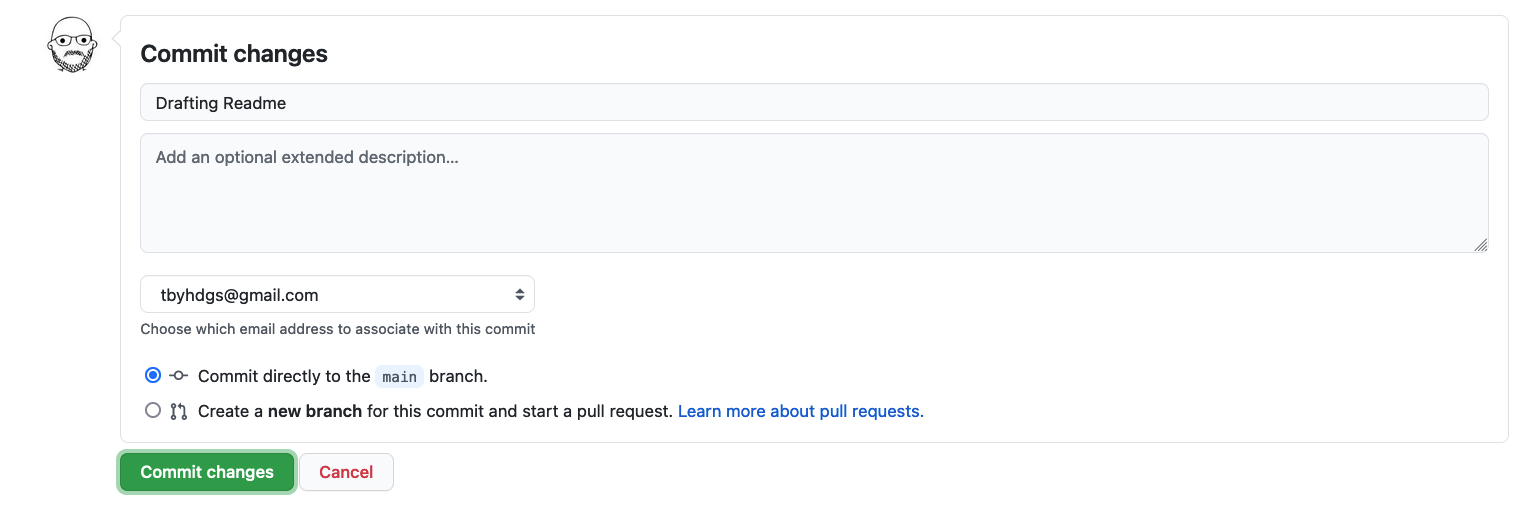

README.md, scroll down a bit and search for a Commit

changes menu at the bottom of the page. After having changed

something, the commit menu looks like this:

Writing a Commit Message

A commit message is a short, descriptive, and specific comment that will help us remember later on what we did and why. When editing in the Github interface, it will suggest a vague message about which file you’ve updated or added. It is best practice to change this message to a short but more informative message about what in the file has changed. This more descriptive message will make it much easier if future you needs to go looking through the history for which commit made a specific change. You can find more about writing commit message in the Software Carpentry Version Control with Git lesson.

Commit this change to the main branch.

Writing Markdown

Now that we know about the editing interface and preview tab of our

projects README.md we can use it as a text editor and

investigate selected Markdown features.

Our README.md already contains vanilla text and two

formatting features:

- Heading

# group-website - Emphasis using

**bold**.

Let’s learn some more Markdown by adding some formatting and see what

happens when we preview it using the preview tab. Add the following to

your README.md file.

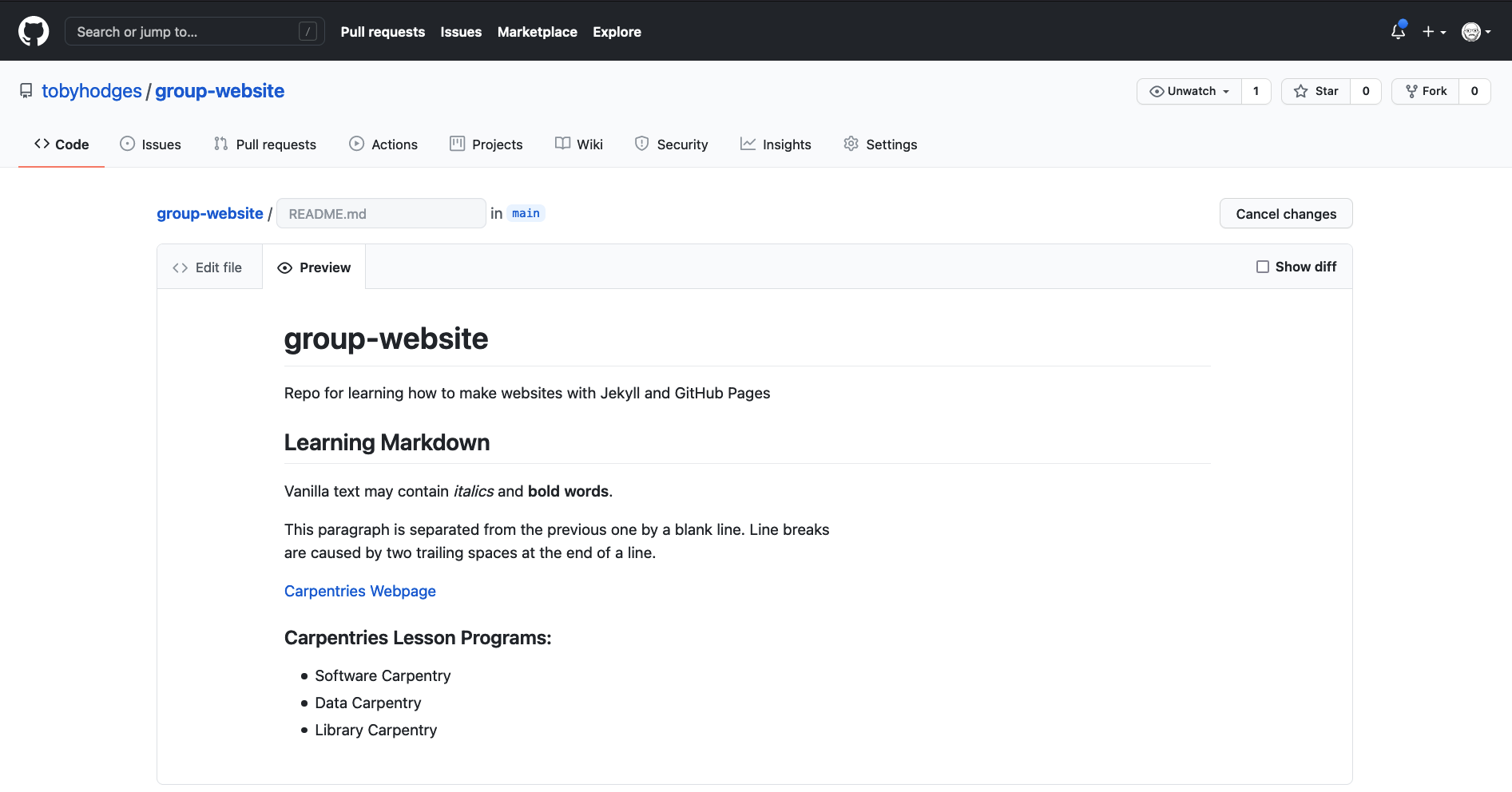

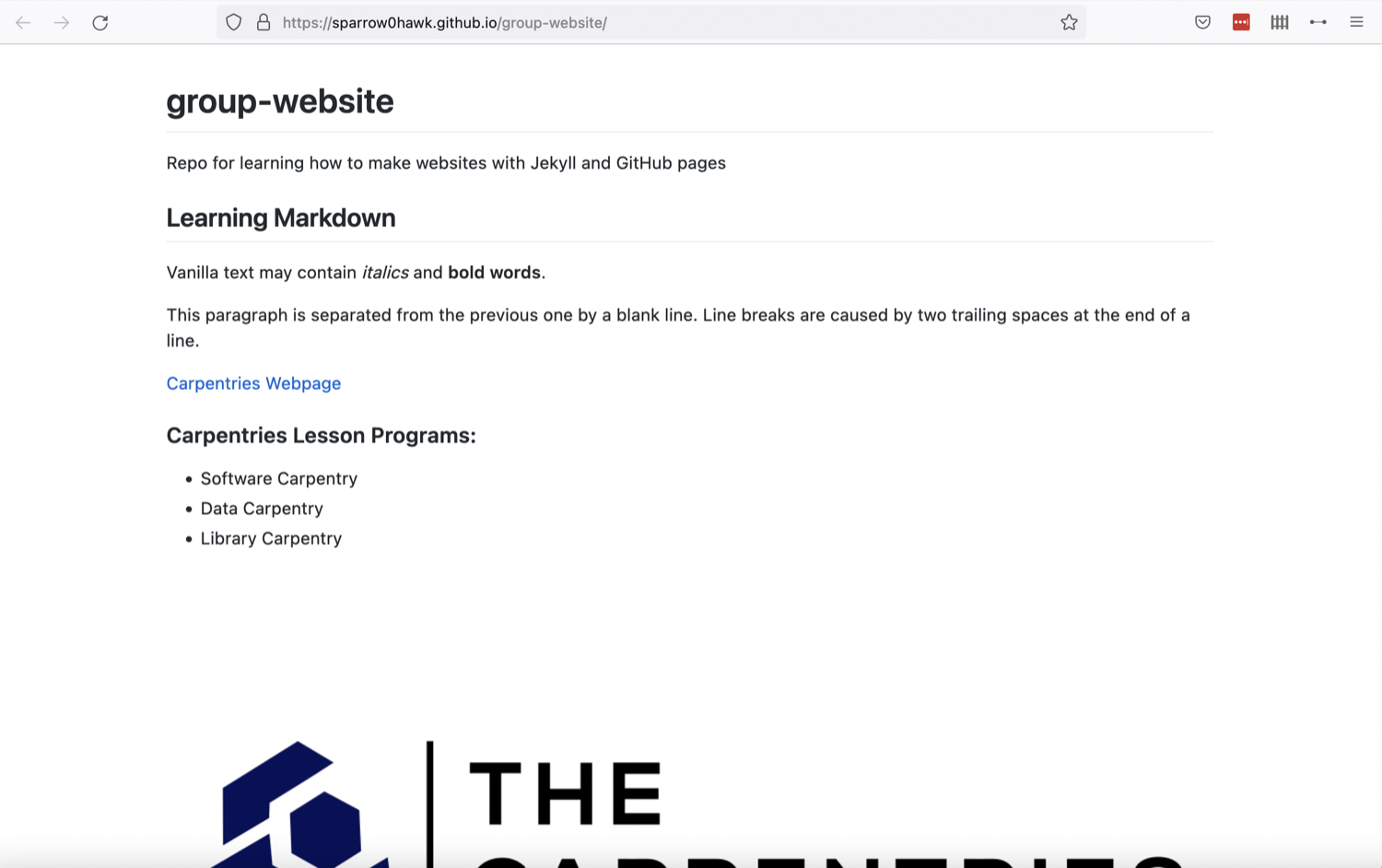

MARKDOWN

# group-website

Repo for learning how to make websites with Jekyll and GitHub pages

## Learning Markdown

Vanilla text may contain *italics* and **bold words**.

This paragraph is separated from the previous one by a blank line.

Line breaks

are caused by two trailing spaces at the end of a line.

[Carpentries Webpage](https://carpentries.org/)

### Carpentries Lesson Programs:

- Software Carpentry

- Data Carpentry

- Library CarpentryYou can then click the preview tab again to see how the formatting renders.

If you click the Show diff checkbox in the right corner,

GitHub will include a preview of differences too - the green bar

indicates added lines, the red bar indicates deleted lines, and yellow -

lines that have been modified.

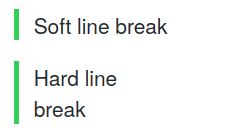

Markdown Trailing Spaces Are Meaningful

In the example above there are two spaces at the end of

Line breaks. These introduce what is called a hard

line break, causing that paragraph to continue in the next line

by adding a <br/> to the generated HTML.

If you break the line in a markdown file but don’t include the two

trailing spaces the generated HTML will continue in the same line

without introducing a <br/>. This is

called a soft line break.

In some cases you may find that soft line breaks do

introduce a <br/>. This can happen when using

different markdown flavors.

See for instance:

That produces:

To keep this addition to our README.md we need to commit

these changes to save them. Scroll down to the bottom of the page, add a

commit message if you wish, and then commit to the main

branch.

Let’s do an exercise to try out writing more markdown.

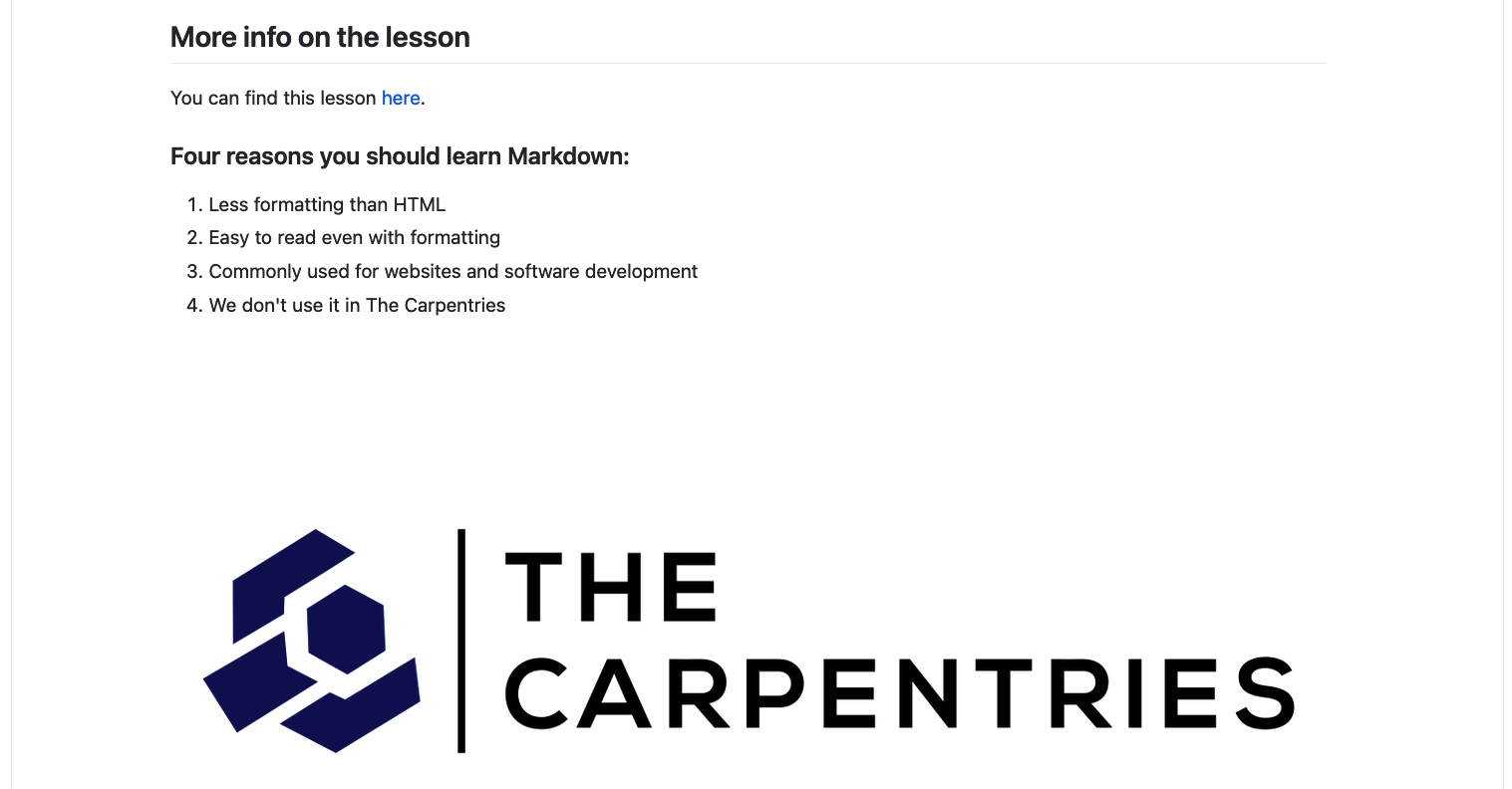

Exercise: Try Out Markdown

Use [this cheatsheet][github-flavored-markdown] to add the following

to your README.md:

- Another second level heading

- Some text under that second level heading that includes an link and

strikethroughtext. - A third level heading

- A numbered list

- Bonus: Add this image https://raw.githubusercontent.com/carpentries/carpentries.org/main/images/TheCarpentries-opengraph.png

For example your markdown might look like the following:

MARKDOWN

## More info on the lesson

You can find this lesson [here](https://carpentries-incubator.github.io/jekyll-pages-novice/).

### Four reasons you should learn Markdown:

1. Less formatting than HTML

2. Easy to read even with formatting

3. Commonly used for websites and software development

4. We ~~don't~~ use it in The Carpentries

Reference-Style Links

Up to now, we have used inline-style links which have the URL inline with the description text, for example:

If you use a link more than once, consider using so called

reference-style links instead. Reference-style links reference

the URL via a label. The label goes into square brackets

[ ] right after the description text of the link and then

later, usually at the bottom of the page, you can connect that label to

the url it references to complete the link. This looks like:

and helps to follow the [DRY principle][dry-principle], avoiding redundant specification of information.

Note about image use and attribution

When using images on your website that you don’t own, it’s important to reuse the content responsibly. This means ensuring that the image owner has given permission for the image to be reused and that the image includes appropriate attribution to the owner. If you’re unsure about the availability of an image you can always contact the owner or check if a license is provided alongside the image which may include conditions for reuse. Anyone can re-use and edit Public Domain images so searching for images in the public domain can be a good way to find images for your website. However, it is still good practice to give credit when possible, even for public domain images.

We will continue to use Markdown and learn more throughout the rest of the lesson. Though later we will find we need HTML again for some features.

Markdown Cheatsheet

Markdown offers a variety of formatting features. Have a look at this [cheatsheet][github-flavored-markdown] to get an overview or look things up.

Markdown Flavours

The initial description of Markdown was informal and contained certain ambiguities so over the years different Markdown implementations and syntax variations (often referred to as “flavours”) appeared to support various syntax features and extensions. As a consequence, the syntax from one variant may not be interpreted as expected in another - you have to be aware which one is being used by a particular platform. Here are a few well-known variants:

- [GitHub-flavored Markdown][github-flavored-markdown] (used on this lesson and by GitHub)

- [GitLab-flavored Markdown][gitlab-flavored-markdown] (used by GitLab)

- [Kramdown][kramdown] (a fast, Ruby, open source implementation released under the MIT licence)

Optional Exercise: Add Your Repository Details to CodiMD

If your instructors are using CodiMD (or HackMD or any other Markdown-based shared document platform) to take notes during this workshop, use Markdown syntax to add a link in that document to the repository you are using to follow along with this lesson. The link text should be your GitHub username, and the target your repository. Your instructors will direct you towards the appropriate location in the document to add your link.

More Markdown Features

Check out our Extras page on Markdown for a more comprehensive overview of Markdown, including how to create fenced code blocks and do syntax highlighting for various languages.

Key Points

- Markdown is an relatively easy way to write formatted text

Content from Hosting Websites on GitHub

Last updated on 2022-11-15 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 40 minutes

Now that you know how to create Markdown files, let’s see how to turn them into Web pages. GitHub has a service just for that called GitHub Pages.

Overview

Questions

- How do I publish my page or a website on the Web via GitHub?

Objectives

- Publish Markdown files as HTML on the Web with GitHub Pages

Publishing a Website With GitHub Pages

GitHub Pages is a free website hosting service by GitHub that takes files (Markdown, HTML, CSS, JavaScript, etc.) from your GitHub repository which is configured as a website, optionally runs the files through a build process, combines them and publishes them as a website. Any changes you do to the files in your website’s GitHub repository will be rendered live in the website.

There are other services available to create and publish websites but one of the main advantages of GitHub Pages is that you can version control your website and therefore keep track of all your changes. This is particularly helpful for collaborating on a project website. GitLab offers very similar services but GitHub pages is the simplest approach.

Let’s continue from the GitHub repository we have created in the

previous episode. One important file you should already have is

README.md, which will become the homepage of your project

website (until we add the index file later on).

Enabling GitHub Pages

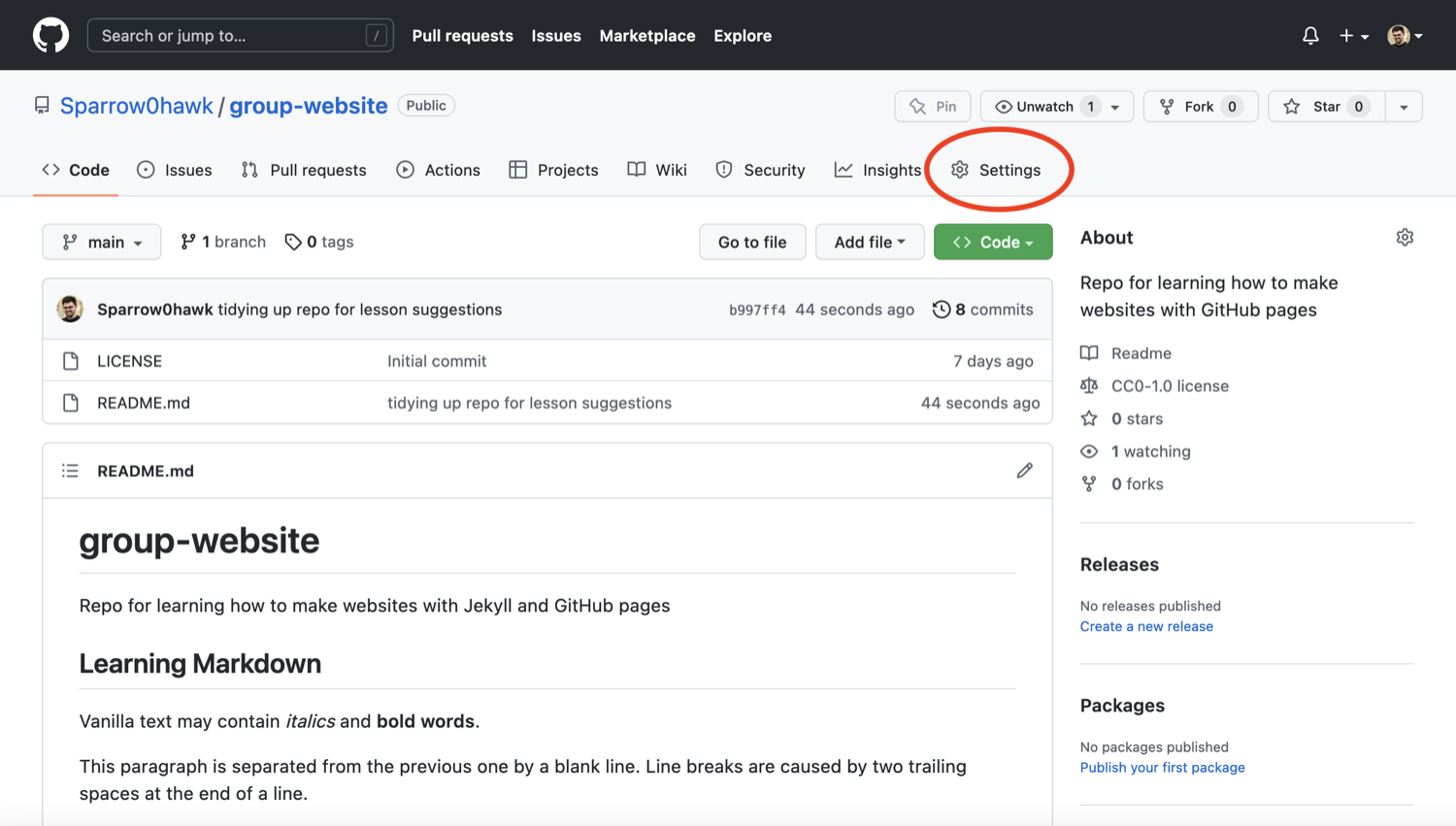

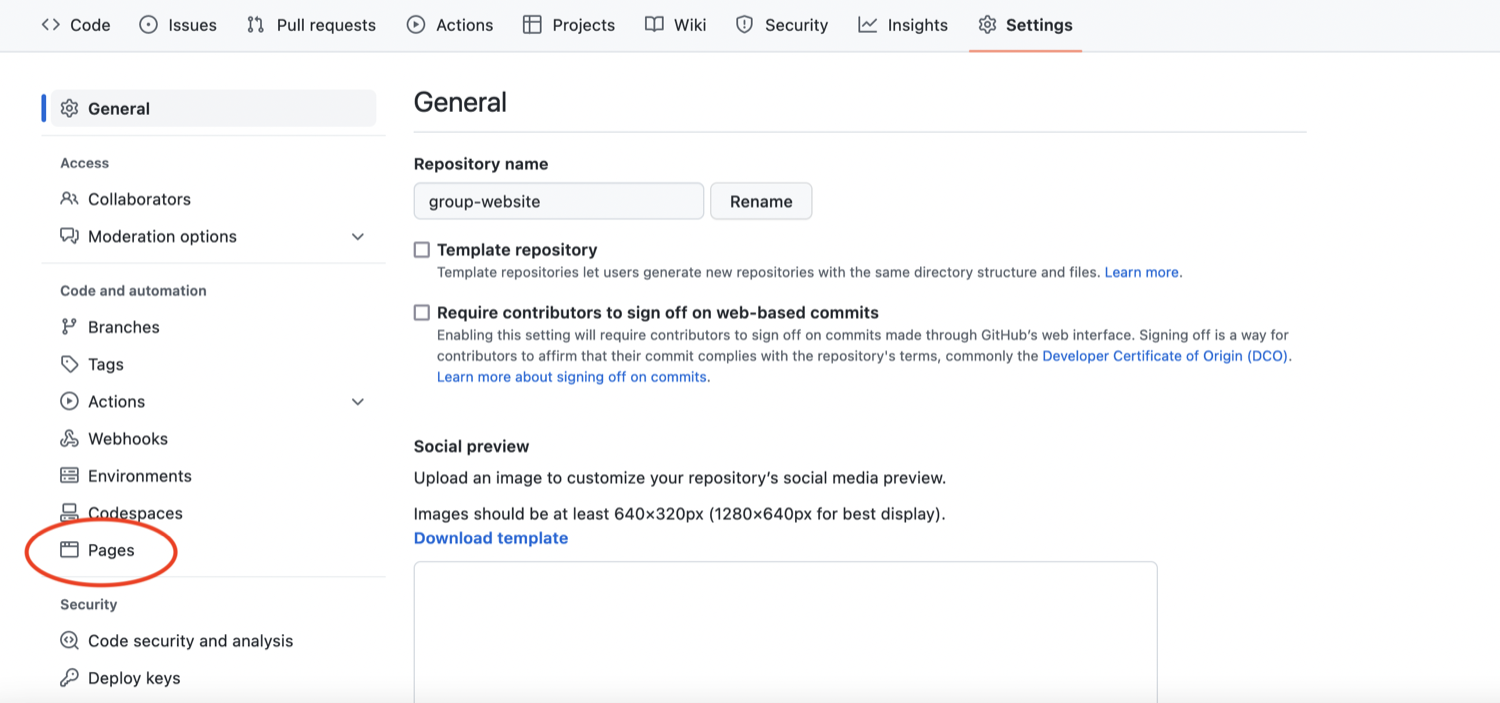

In order to tell GitHub that your repository contains a website that needs rendering you need to configure GitHub Pages settings. You can do so from your repository’s Settings page, as explained below.

You may have noticed that when we created our repository in previous

episode, by default GitHub created a branch called main and

stored our files there. We now need to tell GitHub Pages that this

branch contains our website files.

What Is a Branch?

You may have never heard about Git branches and wonder what they are.

A branch is one version of your project (the files in your repository)

that can contain its own set of commits - you can have many branches

(versions) of your repository. The default branch automatically created

with a new github repository is called main.

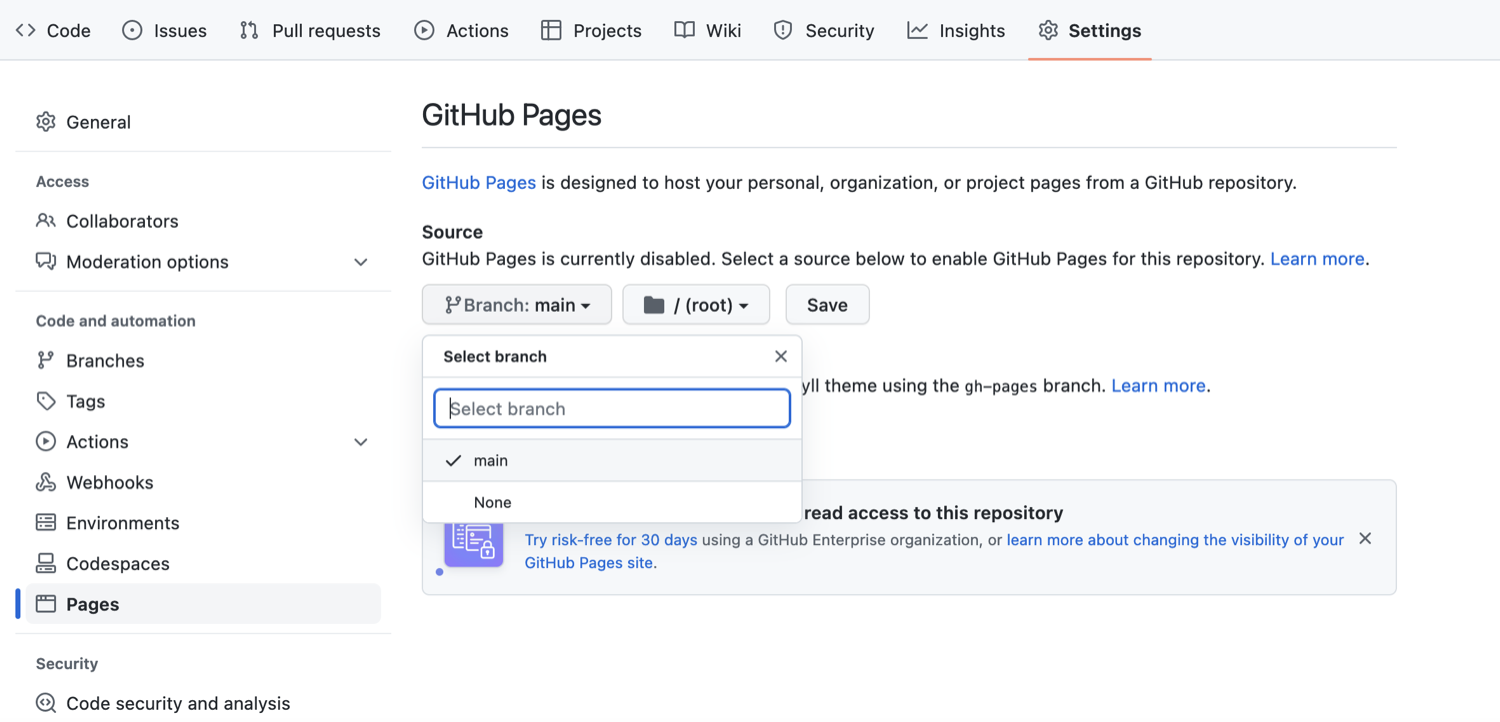

- Click on the repository’s

Settingstab (the one with the little cog/gear icon) as shown on the figure below:

- On the menu on the left hand side, click on

Pages

- You will see that the GitHub Pages settings are currently disabled.

Select branch

mainto tell GitHub which branch to use as a source and clickSaveto enable GitHub Pages for this repository.

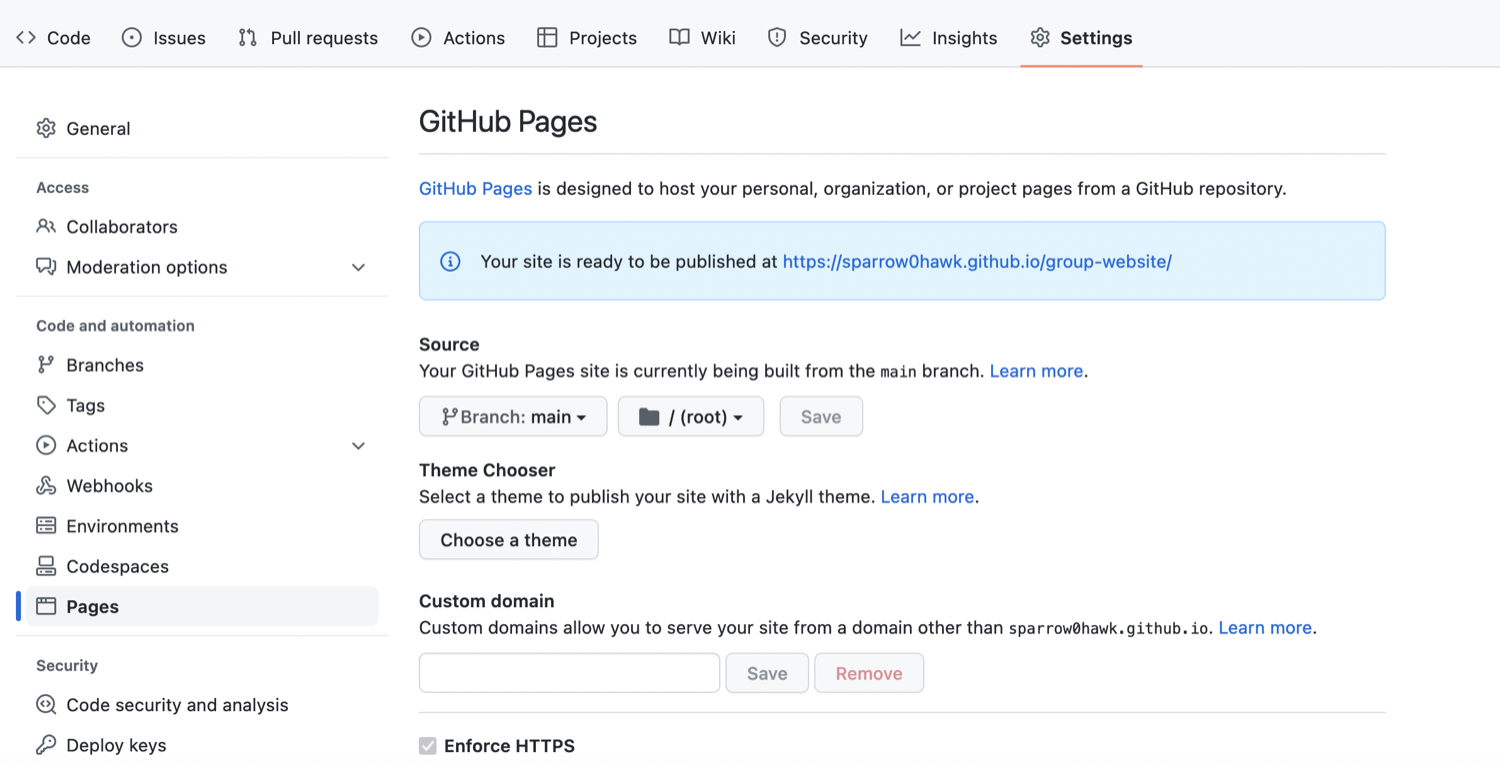

- The link to your repository’s website will appear in the highlighted box above. If you click the link - your default browser will open and show your project website. If this does not happen, you should manually open your favourite web browser and paste the URL.

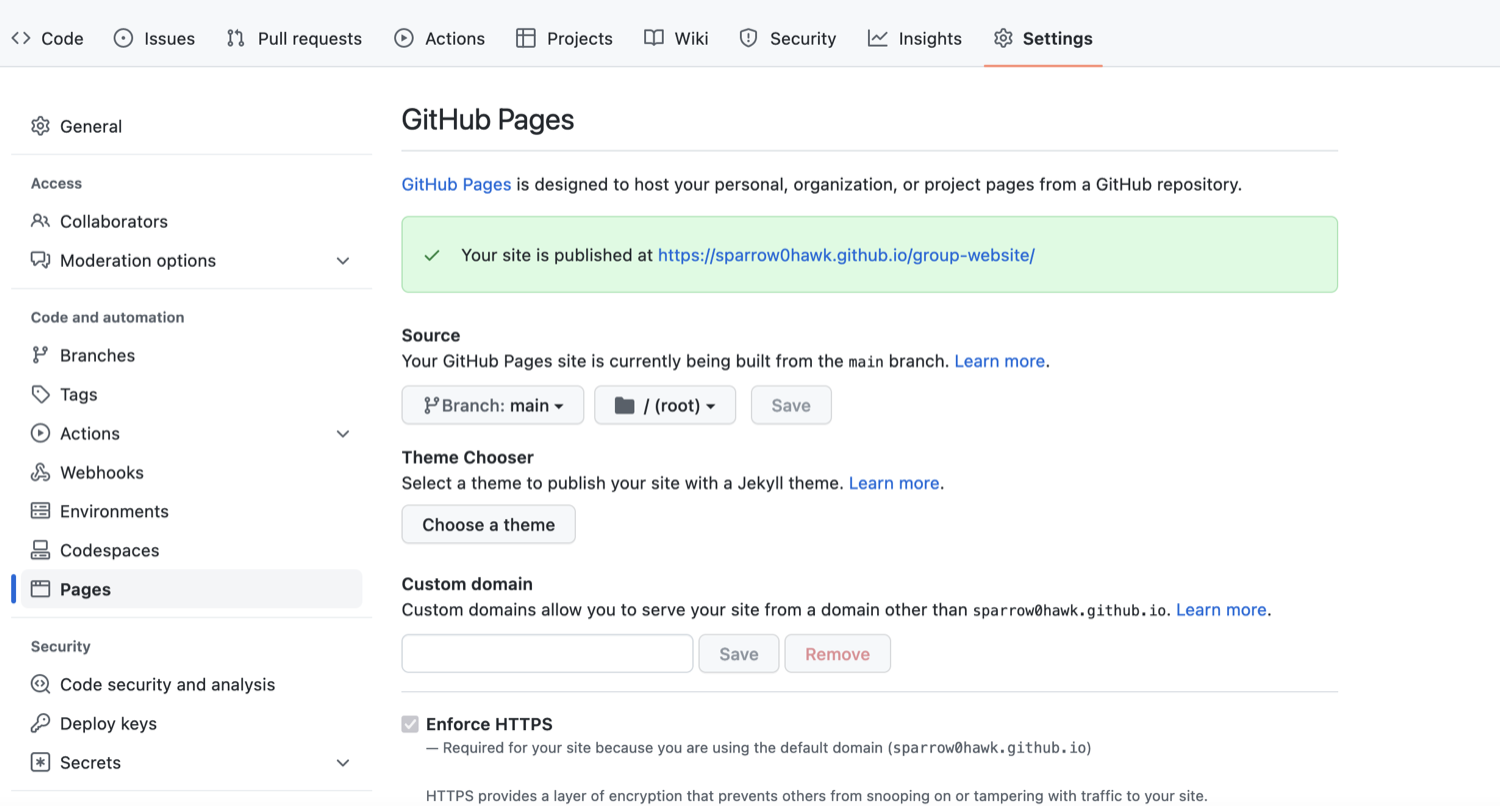

- It may take a while (from a few seconds to a few minutes) for GitHub to compile your website (depending on GitHub’s availability and the complexity of your website) and it may not become visible immediately. You will know it is ready when the link appears in green box with a “tick” in front of the web address (as shown in the figure below).

- Once ready, you should see the contents of the

README.mdfile that we created earlier, rendered as a website.

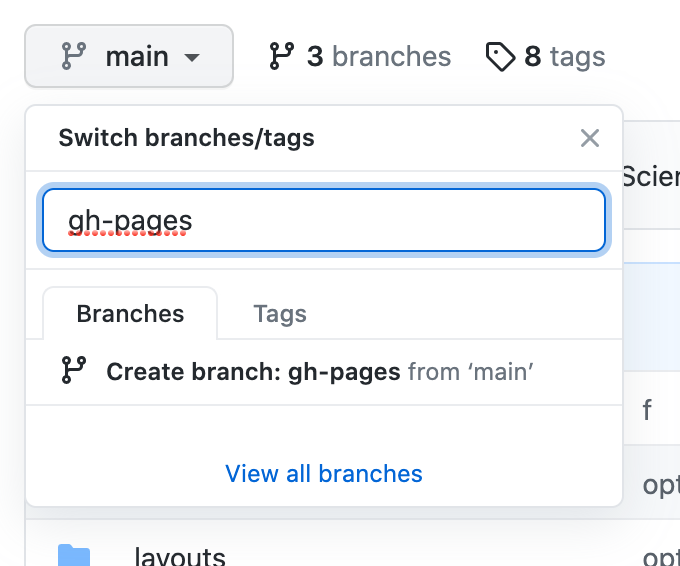

Using Branch gh-pages for

Websites

By convention, GitHub Pages uses branch called gh-pages

to look for the website content. By creating a branch with that name,

you implicitly tell GitHub that you want your content published and you

do not need to configure GitHub Pages in Settings. Once you

create gh-pages from your current branch (typically

main, created by default when you created the repository),

you can then choose to delete the other branch to avoid any confusion

about where your content is stored.

Either of the above two approaches to turning a repository to a

website will give you the same result - the gh-pages

approach is perhaps more common as it favours convention over

configuration.

Understanding GitHub Pages’ URLs

You may have noticed a slightly strange URL for your website appearing in that green box with a “tick” in front of it. This URL was generated by GitHub Pages and is not random. It is formatted as ‘https://GITHUB_USERNAME.github.io/REPOSITORY_NAME’ and is formed by appending:

- your GitHub username or organisation name under which the repository is created (GITHUB_USERNAME)

- ‘.github.io/’ (GitHub’s web hosting domain)

- the repository name (REPOSITORY_NAME)

Because the repository name is unique within one’s personal or organisational GitHub account - this naming convention gives us a way of neatly creating Web addresses for any GitHub repository without any conflicts.

Customising Domain

GitHub Pages supports using custom domains, or changing your site’s URL from the default ‘https://GITHUB_USERNAME.github.io/REPOSITORY_NAME’ to any domain you own. Check out the documentation on configuring a custom domain for your GitHub Pages site.

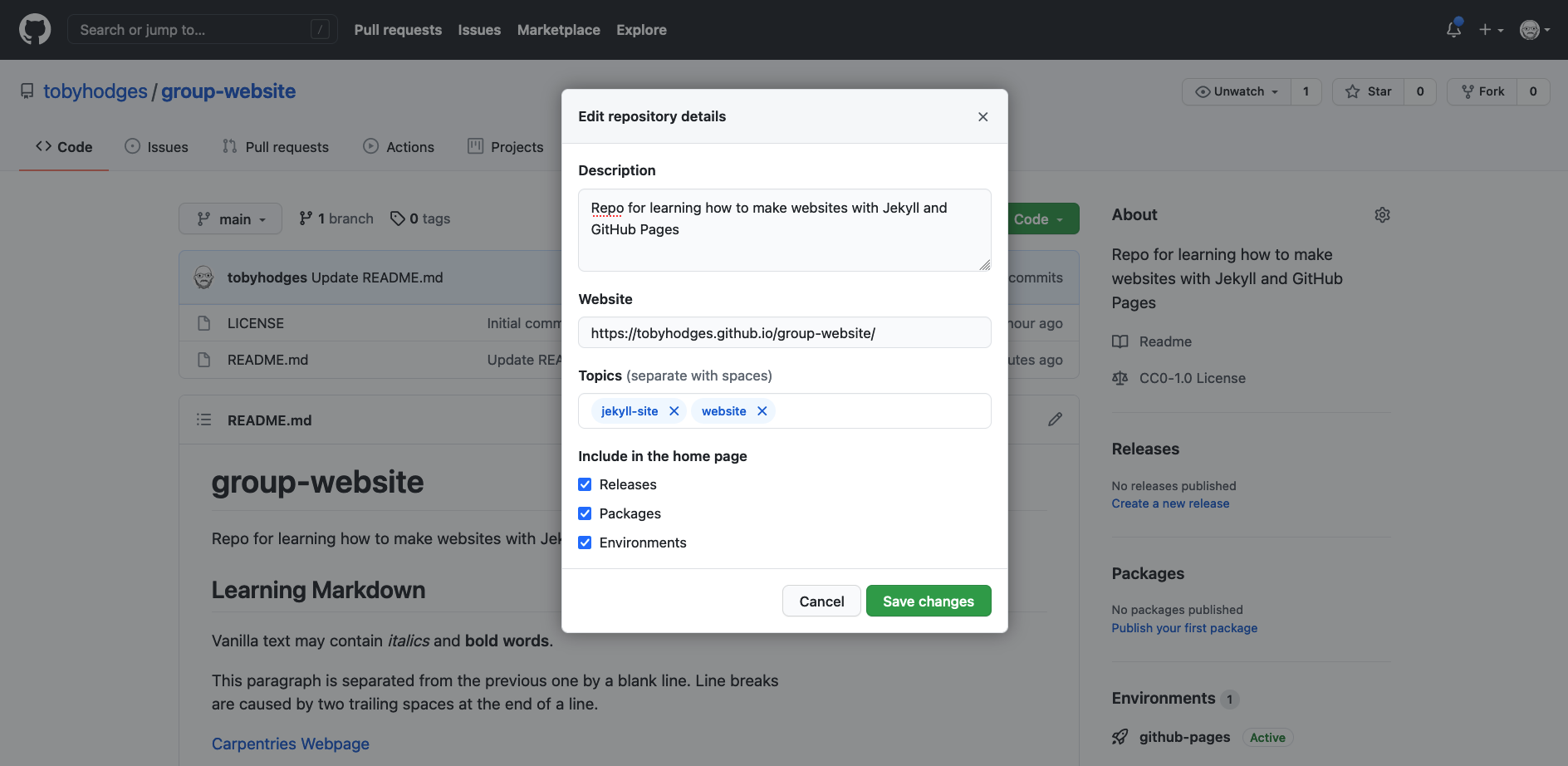

Making Your Pages More Findable

On the right hand side of your repository on GitHub, you can see the

details of your repository under ‘About’. It is good practice to update

your repository details with a brief description. This is also a place

where you can put your repository’s Web URL (as not everyone will have

access to your repository’s Settings to find it) and add

descriptive topics or tags about the content or technologies used in

your repository or project.

You can edit the details of your repository by clicking on the little cog/gear button as shown on the figure below.

By doing this, you add a link to the repository’s website on your repository’s landing page and anyone (including yourself) can access it quickly when visiting your GitHub repository.

Index Page

Up to now, the content of your webpage is identical to what visitors

to your repository on GitHub will see in the project’s

README.md file. It is often better to have different

content in the homepage of your site - aimed at visitors to the website

- than in the README, which is supposed to provide information about the

GitHub repository e.g. license information, local installation

instructions, the structure and configuration of the repository, list of

collaborators/authors, etc. By default, the homepage for a GitHub Pages

website is built from a file called index.md: in the

absence of a file with that name the “fallback” option is to use

README.md, which is why your homepage is currently being

built from that file.

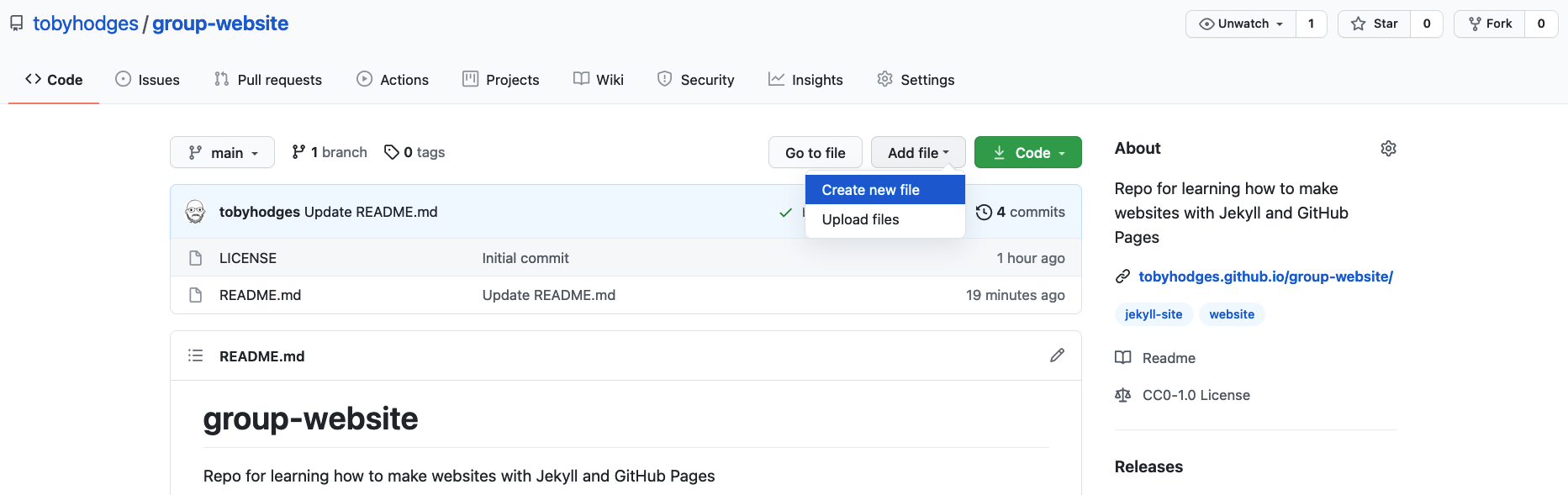

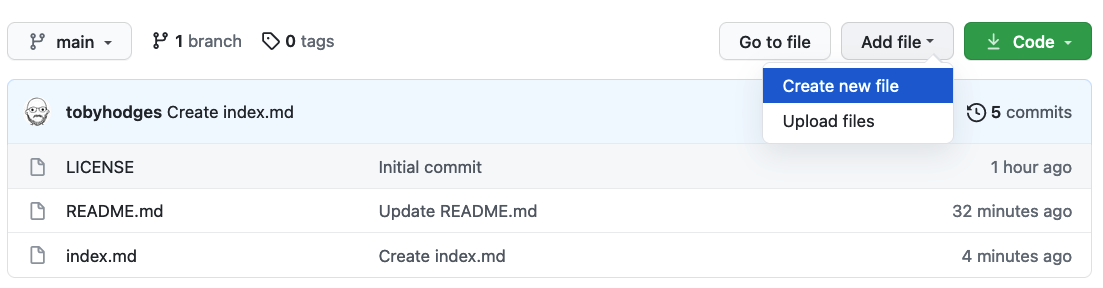

To separate the contents of the repository’s README from the

website’s homepage, create a new file called index.md.

To create a new file from GitHub interface, click the

Add file button and select Create new file

from the dropdown.

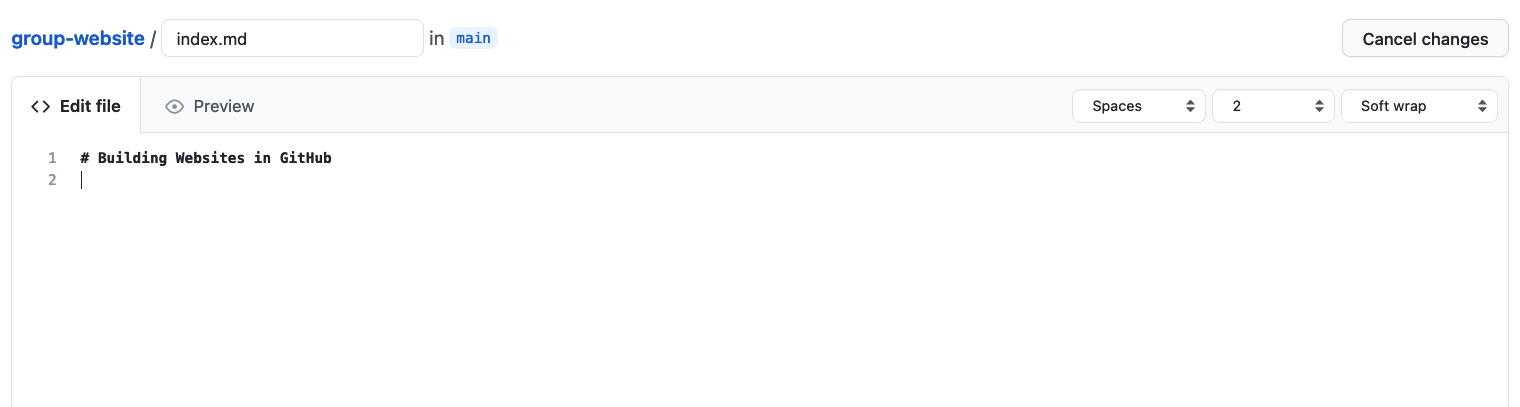

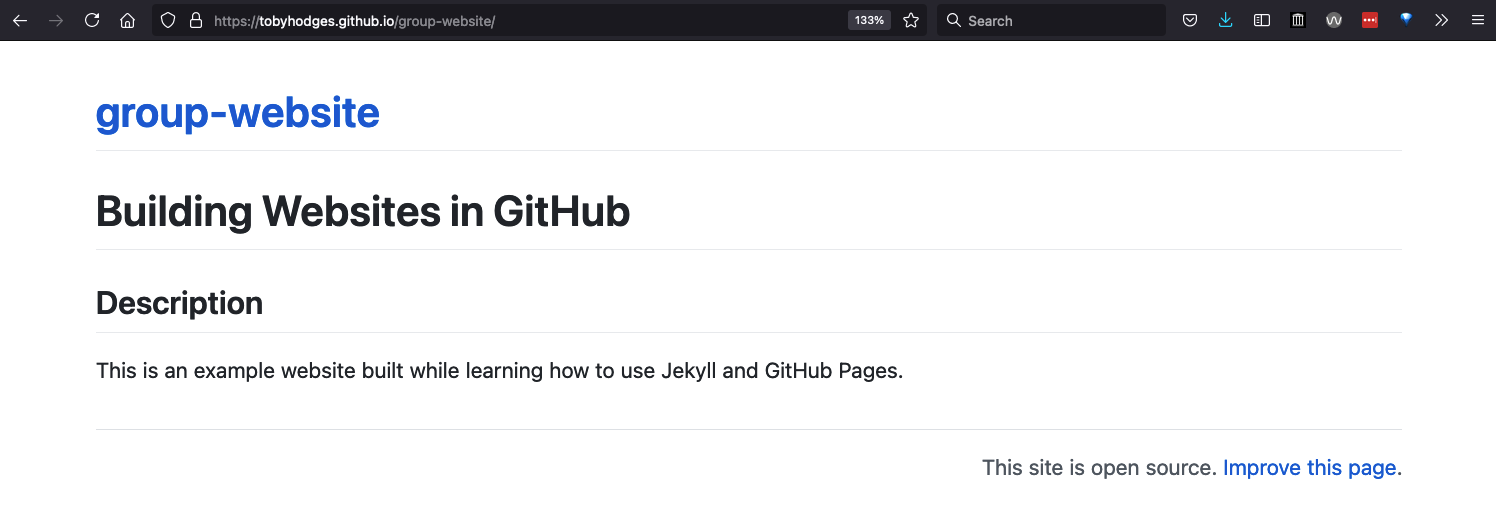

Next, type some text into index.md. As shown below add a

first level header that says

Building Websites in GitHub.

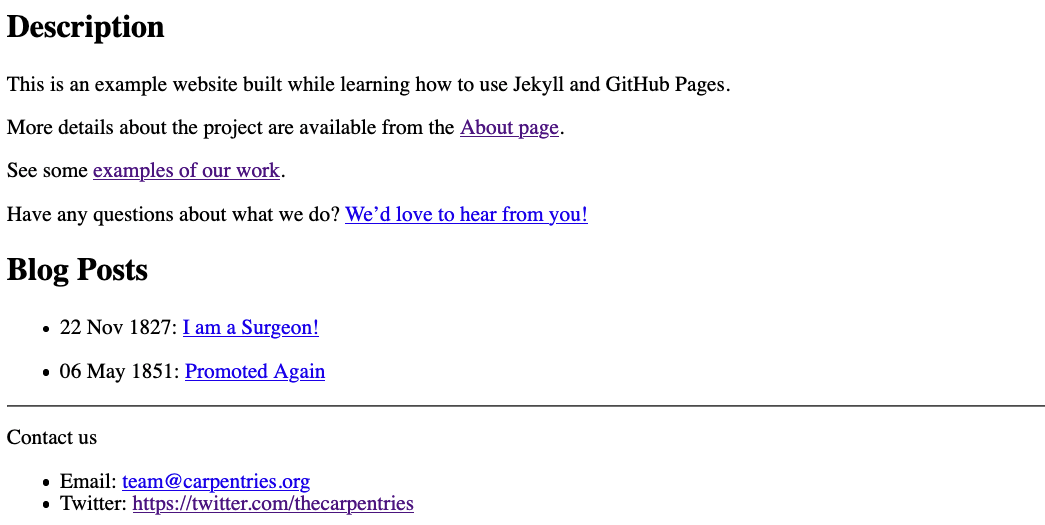

We are now ready to start adding more content to our website. Let’s do some exercises.

Exercise: Add New Content to the Website

Add a new section ‘Description’ to file index.md and add

some description.

- From the GitHub interface, edit file

index.mdand add a new section calledDescriptionto it, with some text about the project. - View the changes on the website.

Both the pages built from README.md and

index.md have been served to us at the “root” of our site:

the page we see when we point our browser to

https://YOURUSERNAME.github.io/REPONAME/. The actual name

of this page is index.html (navigate to

https://YOURUSERNAME.github.io/REPONAME/index.html to see

this for yourself), i.e. the file index.md is converted

by Jekyll to a page called index.html.

As more Markdown files are added to your repository, the same process

will automatically occur for those files too. For example, a file called

contact.md will be converted to contact.html

and cake-recipes.md will become

cake-recipes.html. However, unlike the special

index.html file, which Web servers look for as the default

“landing page” to display when handling a request for a URL with a

trailing forward slash, we must request these pages by name when we want

to view them on the Web. Continuing with the above examples, if we

wanted to visit the cake-recipes.html page, we would need

to point our browser at

https://YOURUSERNAME.github.io/REPONAME/cake-recipes.html,

and https://YOURUSERNAME.github.io/REPONAME/contact.html

for the page built from contact.md.

However, when linking between pages of the same site

(relative linking), GitHub Pages allows us to refer to the name

of the original Markdown file, and handles the URL conversion for us.

This means that, to link to cake-recipes.html from

index.html, we can write a link such as

[Read our recipe for Triple Chocolate Raspberry Surprise Cake and more](cake-recipes.md)

and Jekyll will convert this to the appropriate URL. (It won’t write or

bake the recipe for us, unfortunately.) Relative links can point to

files in other directories too:

recipes/chocolate-salted-caramel-pudding.md and

../local-dentists.md are both valid link targets (assuming

the relevant files exist in your repository).

Exercise: Create Links Between Pages

Create a new file about.md and link to it from

index.md.

- From the GitHub interface, create a new Markdown file called

about.mdand add some content to it. - Add a link to

about.mdfromindex.md. - View the changes on the website.

- Create a new file called

about.mdfrom the GitHub interface: Edit

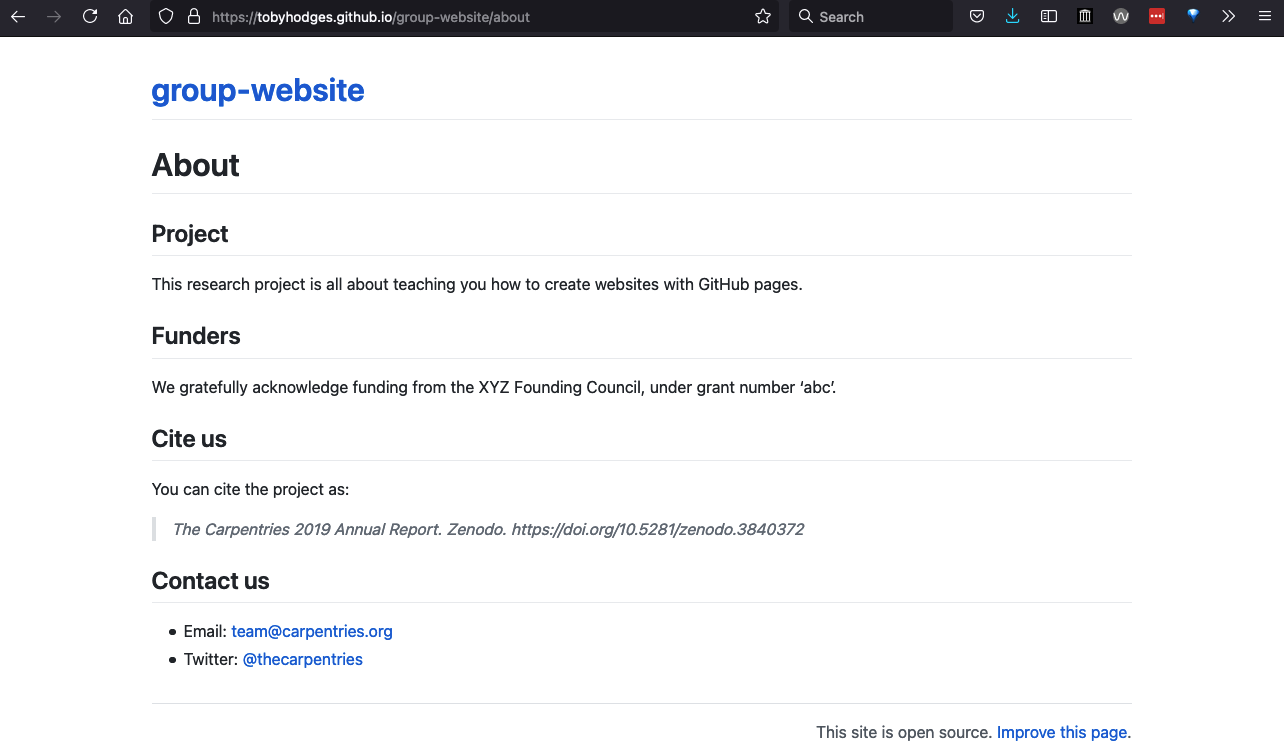

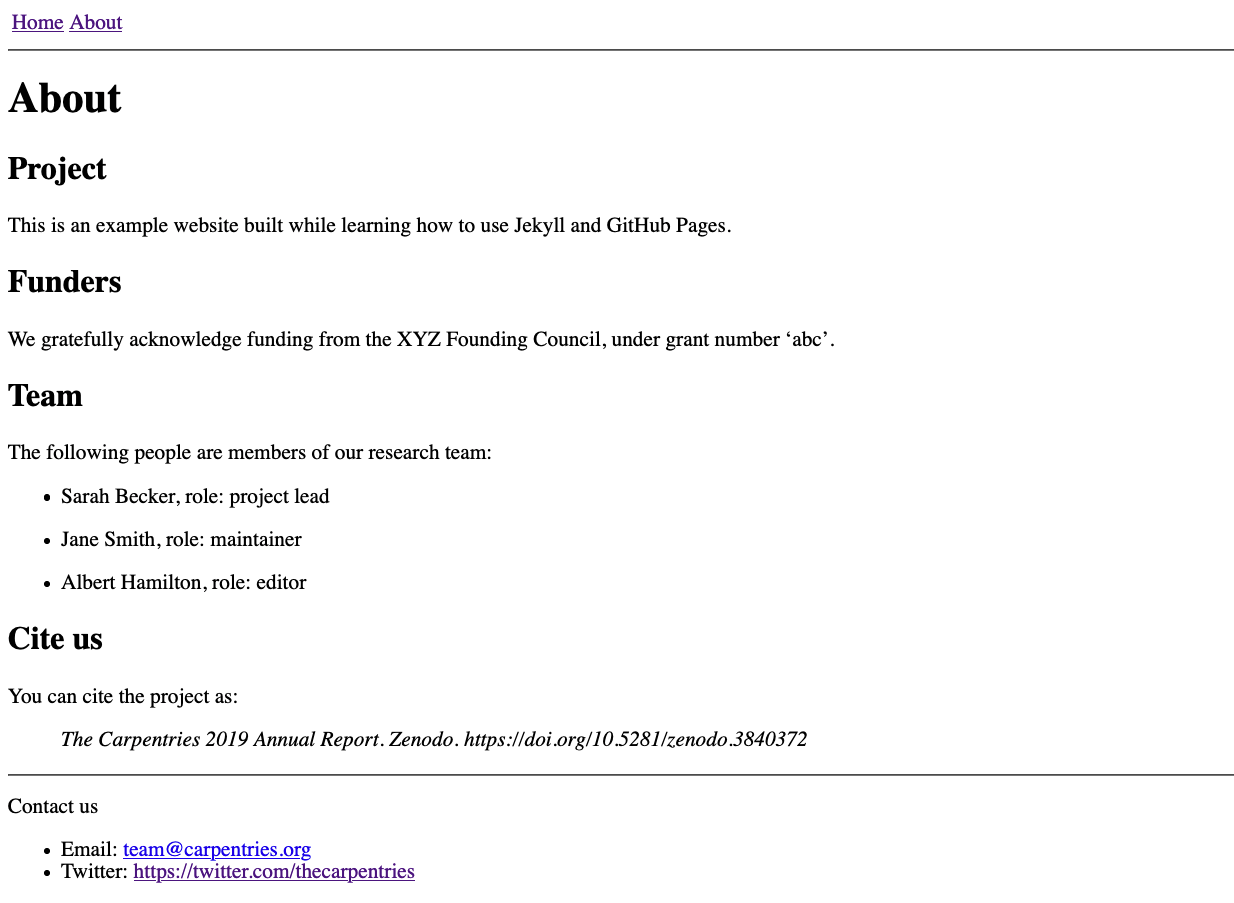

Edit about.mdfile to look something like:

MARKDOWN

# About

## Project

This research project is all about teaching you how to create websites with GitHub pages.

## Funders

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the XYZ Founding Council, under grant number 'abc'.

## Cite us

You can cite the project as:

> *The Carpentries 2019 Annual Report. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3840372*

## Contact us

- Email: [team@carpentries.org](mailto:team@carpentries.org)

- Twitter: [@thecarpentries](https://twitter.com/thecarpentries)Note how we used various Markdown syntax: quoted text

(>), italic font (*) and external links (a

combination of square [] and round brackets ()

containing the link text and mailto or regular Web URLs

respectively).

- Edit

index.mdto add a link toabout.md.

MARKDOWN

# Building Websites in GitHub

## Description

This is an example website built while learning how to use Jekyll and GitHub Pages.

More details about the project are available from the [About page](about).- Go to your website and click the link to ‘About’ page. It should

look like:

Note that the URL has ‘/about’ appended to it - you can use this URL to access the ‘About’ page directly.

Key Points

- GitHub Pages is a static site hosting service that takes files in various formats (Markdown, HTML, CSS, JavaScript, etc.) straight from a repository on GitHub, runs them through its website engine Jekyll, builds them into a website, and publishes them on the Web

- By convention, if you create a branch called

gh-pagesin your repository, it will automatically be published as a website by GitHub - You can configure any branch of a repository to be used for website

(it does not have to be

gh-pages) - GitHub publishes websites on special URLs formatted as ‘https://GITHUB\_USERNAME.github.io/REPOSITORY\_NAME’

Content from Starting With Jekyll

Last updated on 2022-11-15 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 30 minutes

Jekyll is a powerful static site

generator behind GitHub Pages. It creates static HTML website content

out of various files in your repository (Markdown files, CSS style

sheets, page templates/layouts, etc.). This ‘compiled’ content is then

served as your website via the github.io Web domain

(remember your website’s URL from the previous episode?). Jekyll

automatically re-generates all the HTML pages for your website each time

you make a change to your repository.

Overview

Questions

- How can I use values stored in variables in my pages?

- How can I configure global values/settings for my site?

Objectives

- Substitute variable values into page content

- Adjust the configuration of the site and individual pages

- Learn how to identify and correct errors that lead to Jekyll build failures

Jekyll makes managing your website easier because it depends on templates. Templates (or layouts in Jekyll notation) are blueprints that can be reused by multiple pages. For example, instead of repeating the same navigation markup on every page you create (such a header, a footer or a top navigation bar), you can create a Jekyll layout that gets used on all the pages. Otherwise, each time you update a navigation item - you’d have to make edits on every page. We will cover Jekyll layouts in a bit; for now let’s start learning Jekyll and its scripting language called Liquid.

Global Parameters

Jekyll’s main configuration options are specified in a

_config.yml file, which is written in a language called YAML and placed in your site’s root

directory. Parameters configured in _config.yml are global

or site-wide - that means they are accessible in every page of your

website.

YAML

YAML is a human-readable data-serialization language. It is commonly used for configuration files and in applications where text data is being stored or transmitted and it is programming language agnostic.

Let’s create some configuration parameters for our website.

From the GitHub interface, create

_config.ymlfile in your site’s root directory.Add parameters

descriptionandemailto it as:

YAML

description: "This research project develops training materials for reseachers wanting to learn to build project

websites in GitHub with GitHub Pages."

email: "team@carpentries.org"- Commit your changes.

Global configuration settings from _config.yml are made

available as site.PARAMETER_NAME variable in every page

within the website. So, global parameter email we defined

above would be accessed as site.email.

In order to access the parameter’s value within a page, you use

Liquid’s notation to output content by surrounding a variable in curly

braces as {% raw %}{{ variable }}{% endraw %}.

Predefined Global Parameters

In addition to the global parameters you define, Jekyll also makes a

number of useful

predefined site-wide variables available to you within your website:

e.g. {% raw %}{{ site.time }}{% endraw %} (the current

time) or {% raw %}{{ site.pages }}{% endraw %} (a list of

all pages).

Let’s make use of global parameters in our pages.

- Modify

index.mdfile to make use of our global parameters like this:

MARKDOWN

# Building Websites in GitHub

## Description

{% raw %}{{ site.description }}{% endraw %}

More details about the project are available from the [About page](about).

Have any questions about what we do? [We'd love to hear from you!]({% raw %}mailto:{{ site.email }}{% endraw %})- We can use the same parameter in different pages. Let’s reuse

{% raw %}{{ site.description }}{% endraw %}and{% raw %}{{ site.email }}{% endraw %}inabout.mdlike this:

MARKDOWN

# About

## Project

{% raw %}{{ site.description }}{% endraw %}

## Funders

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the XYZ Founding Council, under grant number 'abc'.

## Cite us

You can cite the project as:

> *The Carpentries 2019 Annual Report. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3840372*

## Contact us

- Email: [{% raw %}{{ site.email }}{% endraw %}](mailto:{% raw %}{{ site.email }}{% endraw %})

- Twitter: [@thecarpentries](https://twitter.com/thecarpentries)Go to your website to see the changes.

Note that site parameters will not render nicely when viewing files in GitHub (they will be displayed as text

{% raw %}{{ site.PARAMETER_NAME }}{% endraw %}rather than the parameter’s rendered value) but will in the website.

Exercise: Create a Global Twitter Parameter

In about.md we have a Twitter URL under the ‘Contact us’

section. That’s one piece of information that could go into global

parameters in _config.yml as you may want to repeat it on a

footer of every page. Make changes to your website to extract Twitter

URL as a global parameter.

- Add parameter twitter to

_config.yml:

YAML

description: "This research project develops training materials for reseachers wanting to learn to build project

websites in GitHub with GitHub Pages."

email: "team@carpentries.org"

twitter: "https://twitter.com/thecarpentries"- Make use of the twitter parameter in

about.md:

MARKDOWN

# About

## Project

{% raw %}{{ site.description }}{% endraw %}

## Funders

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the XYZ Founding Council, under grant number 'abc'.

## Cite us

You can cite the project as:

> *The Carpentries 2019 Annual Report. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3840372*

## Contact us

- Email: [{% raw %}{{ site.email }}{% endraw %}](mailto:{% raw %}{{ site.email }}{% endraw %})

- Twitter: [{% raw %}{{ site.twitter }}{% endraw %}]({% raw %}{{ site.twitter }}{% endraw %})- Note that you should not see any changes to your website really. However, you can now access your Twitter URL from any website page, should you need to.

Reuse and Reduce

Jekyll’s global parameters are a useful way to keep all your site-wide configuration in a single place (even if you only use them once). In combination with Jekyll layouts/templates (to be covered in the next episode) they are a great way of creating reusable markup snippets that can be repeated on multiple or even on every page of your website. Reuse helps you reduce the amount of code you have to write.

When Things Go Wrong

So far we have seen how to successfully use Jekyll to produce a website. There are however some situations where Jekyll may fail to do so either due to a typo or missing information.

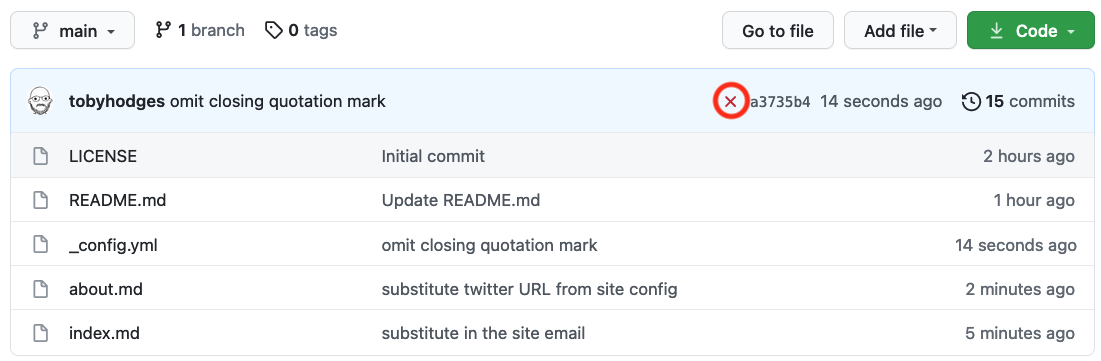

Exercise: Troubleshooting Jekyll

This exercise will help you recognise what common mistakes look like when working with these elements of a Jekyll website.

Edit your _config.yml file and omit a closing quote

" in one of the variables.

For instance, a missing closing quote " in the

twitter variable.

YAML

description: "This research project develops training materials for reseachers wanting to learn to build project

websites in GitHub with GitHub Pages."

email: "team@carpentries.org"

twitter: "https://twitter.com/thecarpentriesIf you navigate your GitHub repository you would be able to see

something break in about.md where we use

{% raw %}{{ site.twitter }}{% endraw %} however, contrary

to what we saw before with invalid Markdown, Jekyll will refuse to build

the website and produce an error message.

We will see after this where to find the error message and identify what caused them.

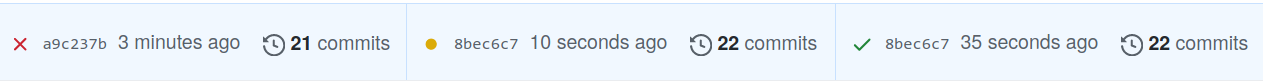

If you were keeping an eye on the GitHub repository page until now, you may have noticed a yellow circle visible when the website is still being processed and a green check mark (✓) when successful. You may have also noticed that in the same location there is now a red cross/X next to the commit message (❌). This indicates that something went wrong with the Jekyll build process after that commit.

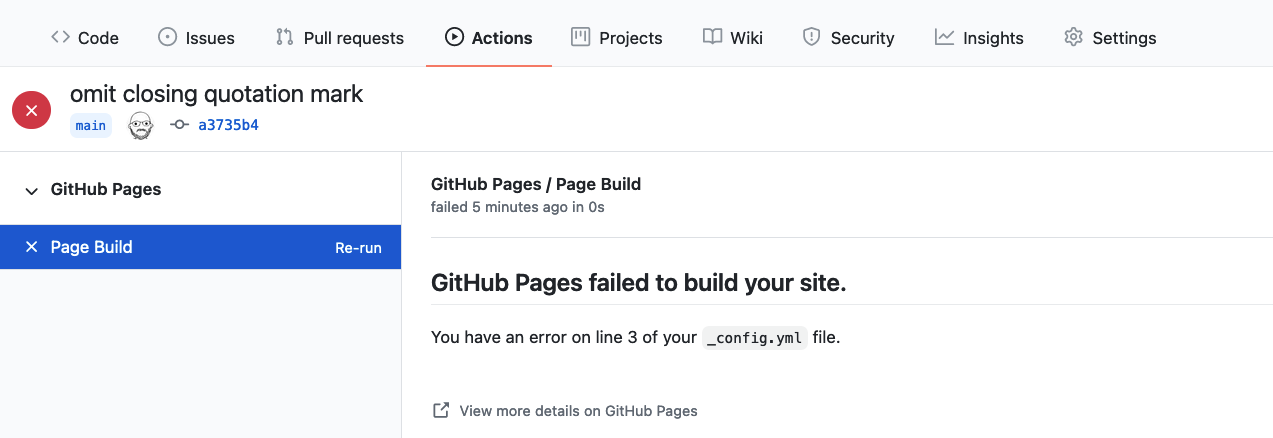

You may also find an email from GitHub in your inbox with details about the error. But let’s look at our repository again. If we click the red cross/X next to the commit message (❌) a little pop-up will appear with additional information.

Visiting the page behind the Details link will give us the information we were missing.

From this page we can see that what caused the failure affected line

5 of the _config.yml file. This matches the line where we

deleted the ". Since this typo prevents Jekyll from

building the page, the process cannot continue.

Failure Will Not Remove Your Website

Given the failure you may be wondering what happened to the website? If you visit the address you will find that the website is still be available.

GitHub will keep your previous version online until the error is fixed and a new build is completed successfully.

Lets go ahead and fix your intentional typo and re-add the missing

":

YAML

description: "This research project develops training materials for reseachers wanting to learn to build project

websites in GitHub with GitHub Pages."

email: "team@carpentries.org"

twitter: "https://twitter.com/thecarpentries"After a few seconds we should see a green checkmark again and our website will be updated.

Local Parameters

In addition to global (site-wide) parameters available via the

site global variable, Jekyll makes local

(page-specific) information available to you via the page

variable. Some of these are pre-defined - like page.title,

which gives you the title of the page that is currently active/being

visited. Others you can define yourself. Check this list of

predefined page parameters.

You can define local parameters using YAML notation within a Markdown

page by including it in a page header and delimiting the header with

triple-dashed lines ---. These headers are called front

matter and are used to set variables and metadata on individual

pages in your Jekyll site.

Front matter

From Jekyll’s website:

Any file that contains a YAML front matter block will be processed by Jekyll as a special file. The front matter must be the first thing in the file and must take the form of valid YAML set between triple-dashed lines.

Global and Local Parameters Are Case Sensitive

It is important to note that the parameters used in the sites are case sensitive. By convention, usually they are all lowercase characters.

Here is an example:

Between these triple-dashed lines, you can overwrite predefined

variables (like page.layout or page.title) or

create custom ones you need locally on the page (like

page.author). These variables will then be available for

you to access using Liquid’s tags

(e.g. {% raw %}{{{% endraw %} page.title {% raw %}}}{% endraw %}

) further down in the file and also in any files that include this one.

Note that these variables are only accessible on that page. You will get

an error if you try to reference a page.variable that was

defined on a different page.

Exercise: Practice With Local Variables

Let’s practice making and using local variables. Think of a local

variable you may want to use only in your about.md or

index.md page. If you cannot think of any, create a local

variable called ‘lesson-example’ with the value of ‘https://carpentries.github.io/lesson-example/’

and reference it in your index.md.

What did you add to your index.md to create this

variable? Where did you add the front matter in your

index.md? How did you reference that variable?

Create a YAML header at the very top of index.md and add

the lesson-example variable in between the triple-dash

delimiters. You can then reference the value within your

index.md page as

{% raw %}{{{% endraw %} page.lesson-example {% raw %}}}{% endraw %}.

Your file should now look like:

MARKDOWN

---

lesson-example: "https://carpentries.github.io/lesson-example/"

---

# Building Websites in GitHub

## Description

{% raw %}{{ site.description }}{% endraw %}

More details about the project are available from the [About page](about).

See some [examples of our work]({% raw %}{{{% endraw %} page.lesson-example {% raw %}}}{% endraw %}).

Have any questions about what we do? [We'd love to hear from you!]({% raw %}mailto:{{ site.email }}{% endraw %})Note that this variable is not accessible from about.md

page and is local to index.md.

Exercise: Practice With Troubleshooting

Sometimes typos happen and can make your website change in surprising ways. Let’s experiment with some possible issues that might come up and see what happens.

Try the changes listed below on your index.md file and

see what happens when the page renders. You will want to correct the

previous mistake each time.

- Use a global or local variable that you didn’t define first.

- Leave the dash off the end of the YAML header.

- Don’t put a space between the YAML header and the rest of the page

- Put the YAML header in a different location in the page.

- The place where you used the undefined variable is blank but otherwise no error. Example:

- The header shows somewhat in the file and the variable that was defined goes to the index page intead of the link we set.

MARKDOWN

---

lesson-example: "https://carpentries.github.io/lesson-example/"

Examples of our work can be found at: {% raw %}{{ page.lesson-example }}{% endraw %}- This doesn’t seem to affect our page but can often make more complex pages break.

MARKDOWN

---

lesson-example: "https://carpentries.github.io/lesson-example/"

---

Examples of our work can be found at: {% raw %}{{ page.lesson-example }}{% endraw %}- This also makes the header somewhat show in the page and breaks the variable link we created.

Exercise: Practice With Troubleshooting (continued)

Note: Be sure to fix any errors you intentionally introduced in your page before moving on.

Key Points

- Variables can be defined globally in

_config.ymlor locally within YAML header (front matter) of a page - Variable values can be substituted into page content with Liquid

notation:

{{ variable }} - Global variables are accessible from any page of your website; local variables can only be accessed within the page in which they were defined (and any pages that include this page)

- Errors can happen but Jekyll will often tell us what’s wrong

Content from Reusing Blocks of Content

Last updated on 2022-11-15 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 75 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can I reuse the same chunks of material in multiple pages?

Objectives

- Create reusable blocks of content and insert them into pages

In the previous episode, we discussed the benefits of using global and local variables to reuse values throughout our pages. However, repeated use of content in and across websites is usually not limited to individual values such as email addresses and social media handles.

Exercise: What Gets Reused?

Look at the two pages linked below, and browse some other pages on the same site.

- [The Software Sustainability Institute][ssi-homepage]

- [DiverseKids Book Store][diversekids]

What content is being reused between pages on these sites? Pair up and compare your partner’s notes with your own. Can you identify any common type(s) of content that is being reused in these sites?

The Software Sustainability Institute website reuses many structural elements, such as the page header (containing the “top menu,” the institute’s logo, links to social media, etc) and footer (containing copyright and licensing information, links to the privacy policy and accessibility statement, a form to subscribe to the institute’s newsletter, etc). Elsewhere, blocks of text and images are reused in the main body of multiple pages, e.g. blog and news posts all end with a description of how the reader can contact the SSI to discuss the content.

The DiverseKids site has the same kind of shared header and footer on each page: this is a common theme across most websites, helping to improve navigation and other aspects of the user experience and achieve consistent “branding” across the whole site. The books listed under each category include a title, a price, and cover image. The category links themselves are also shared across each page, probably generated from the existing categories of books in the collection, and updated automatically when a category is added or removed.

The most commonly reused content is structural: menus and branding information used to present a consistent and recognisable interface to the user regardless of which specific page of the site they’re visiting. We’ll look more at that in the next episode. But some content, such as contact statements and post/product listings, can be reused in the body of pages. The motivation for reusing content like this is that, if you need to update that content - changing the contact address, updating a price or picture associated with a listing, and so on - you need only change this information in one place for the update to be propagated across the whole site. This is related to the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle of good practice in programming.

DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) Principle

DRY principle is one of the basic principles of software development aimed at reducing repetition of information.

As far as we know, the sites linked in the previous exercise aren’t built with Jekyll. But the principles behind reusing content apply regardless of the particular framework being used to build the site.

Reusing Site Navigation Header

Let’s look at an example of how we can create a block of common

content and reuse it in multiple pages on our site. Websites typically

have some navigation links at the top of each page to help visitors

navigate to various portions of the site. To make these links appear

above every page on our site, we could add the same code immediately

after the YAML header of each Markdown file in our repository. But if we

wanted to adjust the menu - adjust the navigation link target, add a new

navigation link, remove a link, etc. - we would need to make the same

adjustment on every page. This is both time-consuming and error-prone:

it would be easy to accidentally mistype a link or forget to update one

of the files. Instead, we can go some way to avoid this hassle by using

some magic that Jekyll provides: include tags.

To demonstrate this, we will save an HTML snippet for creating

navigation links into a new file called navigation.html in

a new folder called _includes within our repository. The

folder _includes has special meaning to Jekyll - it tells

Jekyll where to look for code snippets that can be reused (included) in

other parts of the website.

Click “Create new file” under the “Add file” dropdown on your repository homepage

In the “Name your file…” box, type

_includes/. As you enter the “/” after the folder name “_includes”, the folder is automatically inserted in the path displayed in front of the box for naming the file you are adding.You can then name the file

navigation.htmland, when you commit the changes, the_includesfolder will have been added to your repository too.Insert the following HTML snippet into

navigation.htmland commit the changes:

HTML

{% raw %}<table>

<tr>

<td><a href=".">Home</a></td>

<td><a href="about">About</a></td>

</tr>

</table>

<hr>{% endraw %}The snippet will create a table with a single row with two links followed by a horizontal line separator.

- Now insert the following

includedirective at the beginning ofindex.md:

MARKDOWN

{% raw %}---

lesson-example: "https://carpentries.github.io/lesson-example/"

---

{% include navigation.html %}

# Building Websites in GitHub

## Description

{{ site.description }}

More details about the project are available from the [About page](about).

See some [examples of our work]({{ page.lesson-example }}).

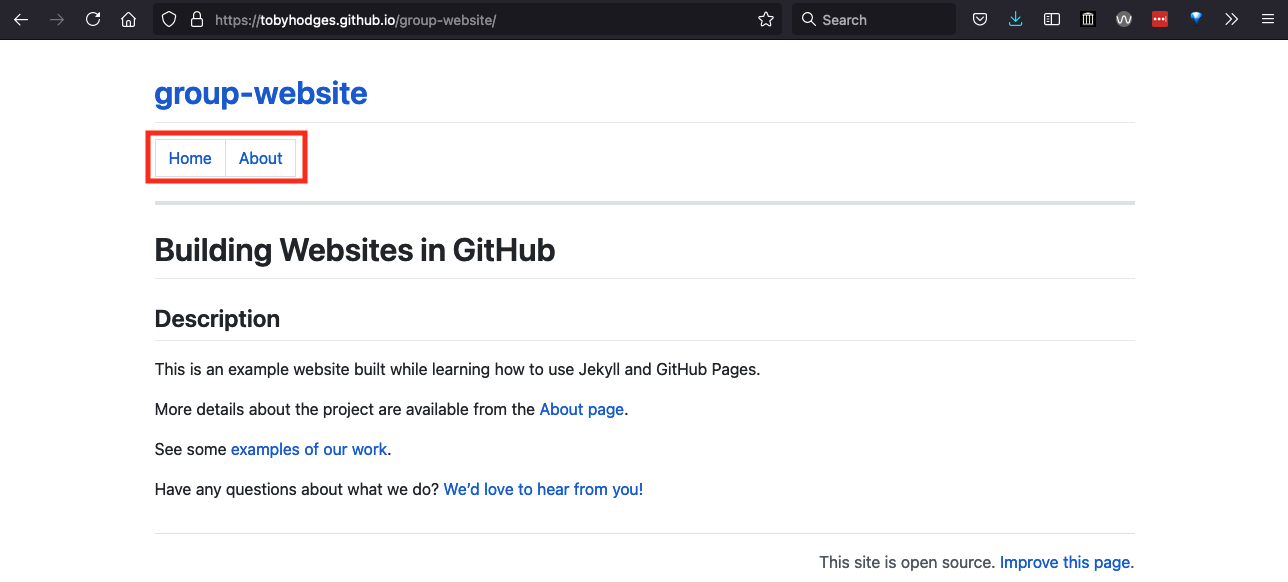

Have any questions about what we do? [We'd love to hear from you!](mailto:{{ site.email }}){% endraw %}Refresh the index.html page and, barring any typos,

e.g. in the name of the file, you should see the navigation links on the

top of the page.

You can add the same include tag at the top of all the

other Markdown files for your site to get the same navigation section

displayed on every page.

Insert the include directive at the top of

about.md so that it now looks as follows:

MARKDOWN

{% raw %}{% include navigation.html %}{% endraw %}

# About

## Project

{% raw %}{{ site.description }}{% endraw %}

## Funders

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the XYZ Founding Council, under grant number 'abc'.

## Cite us

You can cite the project as:

> *The Carpentries 2019 Annual Report. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3840372*

## Contact us

- Email: [{% raw %}{{ site.email }}{% endraw %}](mailto:{% raw %}{{ site.email }}{% endraw %})

- Twitter: [{% raw %}{{ site.twitter }}]({{ site.twitter }}{% endraw %})The include tag can be used to insert the Markdown or

HTML contained in any file saved within _includes

directory: provide the path to that file relative to

_includes/ and Jekyll will substitute the contents into the

page before rendering it as HTML. Like the _config.yml file

that contains the configuration for your Jekyll site, the

_includes folder has a name beginning with an underscore to

show that it has a special meaning to Jekyll. We will see another

example of this shortly.

Why Not Use Variables?

We must place our blocks of content for inclusion in separate files

because Jekyll does not support substitution of variables within

variables. If you’d like to investigate further, you might try

creating a global variable in your site’s _config.yml which

includes a call to another variable in its value, e.g.

social: "{% raw %}Follow us on [Twitter]({{site.twitter}}){% endraw %}",

and using it in a page

({% raw %}{{site.social}}{% endraw %} for the example

above).

Reusing Footer

The last line of about.md includes contact details -

this is the kind of information you might want to reuse in multiple

places throughout your site as a footer.

MARKDOWN

## Contact us

- Email: [{% raw %}{{ site.email }}{% endraw %}](mailto:{% raw %}{{ site.email }}{% endraw %})

- Twitter: [{% raw %}{{ site.twitter }}{% endraw %}]({% raw %}{{ site.twitter }}{% endraw %})Let’s convert the above Markdown snippet into HTML as shown below and

reuse it in index.md and about.md files. We

will explain why we need the file to be in HTML rather than Markdown

shortly.

HTML

<hr>

<p>Contact us</p>

<ul>

{% raw %}<li>Email: <a href="mailto:{{ site.email }}">{{ site.email }}</a></li>{% endraw %}

{% raw %}<li>Twitter: <a href="{{ site.twitter }}">{{ site.twitter }}</a></li>{% endraw %}

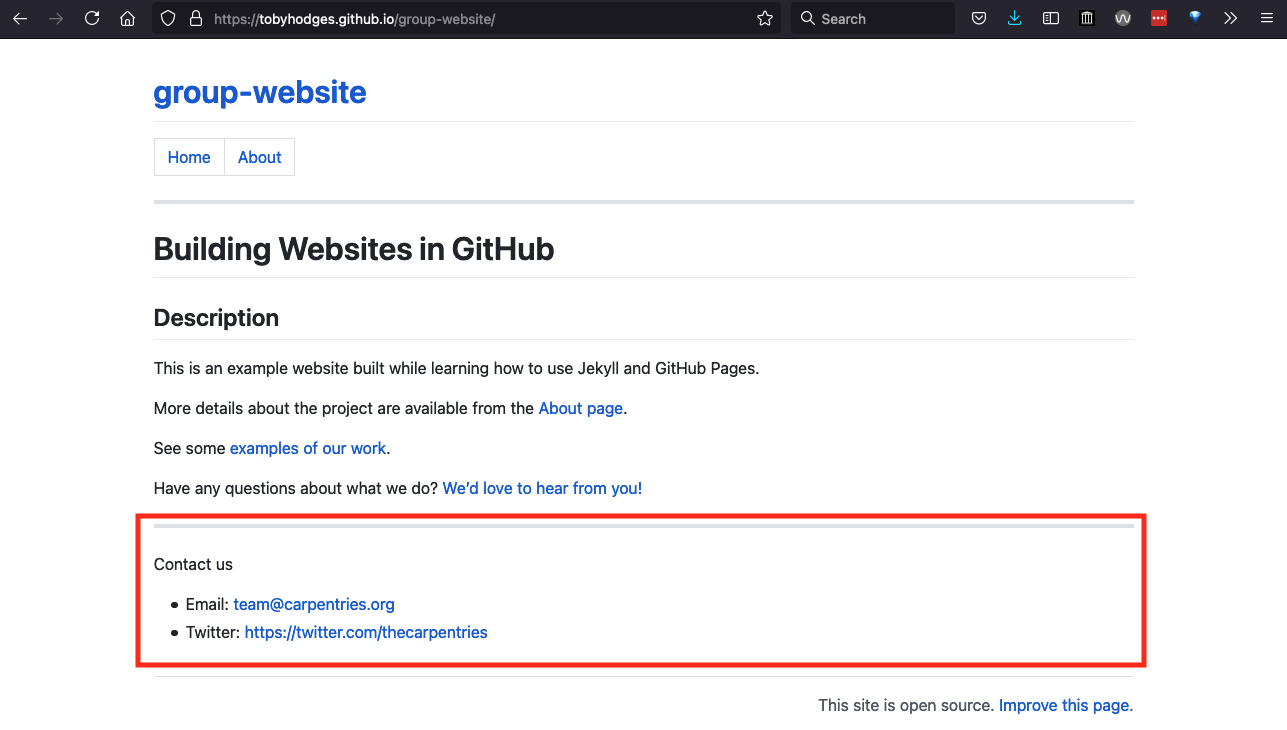

</ul>This HTML snippet will create a horizontal line separator followed by an unordered list with two elements: a contact email address and the Twitter URL wrapped as links using the anchor tag.

Create a file called

footer.htmlinside the_includesfolder to contain the footer HTML snippet.Add the line:

at the bottom of both index.md and about.md

(replacing the equivalent contact section where present).

After refreshing any of these two pages - you should see a horizontal line separating the main page content from the footer of the page which now contains contact information.

This is another example of how we can create a block of common

content and reuse it in multiple pages on our site by using Jekyll’s

include directive and placing code snippets in the

_includes directory (where Jekyll looks for them by name by

convention).

Reusing Link References

You can use include tags to help minimise the effort

required to keep links up-to-date across your site. In the Authoring with Markdown

section, we learned about writing reference-style links in Markdown,

e.g. [link text][link-target] in the body of the file with

a corresponding [link-target]: https://carpentries.org link

reference (usually all such references are kept at the bottom of the

file). Using include tags, the link references for every

page on your site can be stored in a file in the _includes

folder (we recommend the name _includes/links.md) and

inserted into the end of each page. With this approach, any time you

need to update one of these link references, e.g. if the URL changes to

your host institute website, you only need to change the URL in

_includes/links.md to update the target of all the relevant

links across your site.

Key Points

- The content of files in the

_includes/directory can be inserted into a page with{ % include file_name % }

Content from Page Layouts

Last updated on 2022-11-15 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 55 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can I design the layout for all pages on my site?

- Where can I find pre-built themes for my site?

- How can I create new layouts based on those I already have?

Objectives

- Apply a template layout to a page

- Find and implement pre-existing themes to determine the style of a site

- Create new page templates that inherit from existing layouts

Elements that will appear on every page across our website, like the

banner image we included in our pages in the previous section, form part

of the structure of the page: unlike the content specific to each page,

these structural elements do not change from page to page. As such,

although the include tags reduce the pain endured when

adjusting that repeated content, it is not good practice to

include the same content over and over again. This

structure can instead be defined within the layout of the pages

of the site.

Common elements found in a layout are logos, banners, navigation menus, footer content such as copyright and licensing information: material often found at the very top or very bottom of a webpage.

Defining a Layout

Jekyll layouts are defined as HTML files in a special

_layouts folder. We will want our navigational links to

appear on every page of our site so, instead of using an

include tag on each page individually, we should add it to

the layout used for each page. Just like our site’s pages, layouts can

include blocks defined in other files, but the catch is

that these must also be HTML (remember the last exercise when we asked

you to create a footer in HTML instead of Markdown?).

We will now define a new page layout called default,

which we will save in a file _layouts/default.html. Having

defined our navigational links in a separate file, we will start with a

layout file that only includes these links:

You have just defined the first layout for pages on your site. Congratulations!

Add layout: default to the YAML front matter of

index.md to apply this layout to your site’s home page,

then do the same in the front matter of about.md. When you

reload your site’s homepage (or any page you applied the layout to), you

will see that there is good news and bad news: The good news: the

navigation links are there again; the bad: all the other page content

has disappeared!

The page content is missing because we haven’t yet told Jekyll where

to put it. To do that we need to add the special content

variable into the layout file:

We can use the content variable to tell Jekyll where it

should place all the content defined in the Markdown of the

page within this layout. If we make the change shown in the

example above to _layouts/default.html and reload our

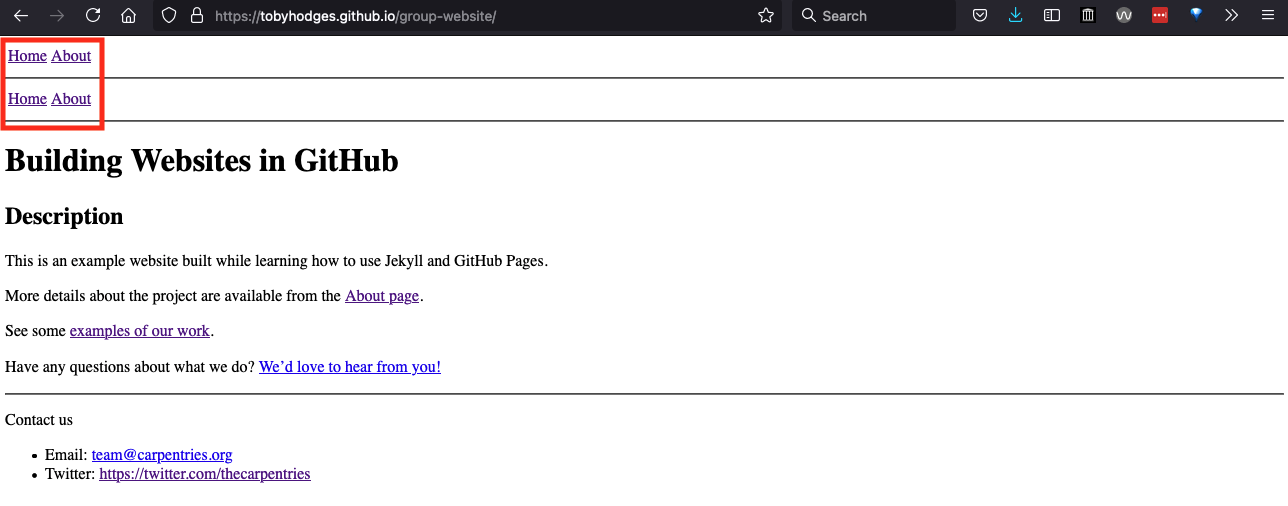

site’s homepage, we now see the page content has returned but we have

two more problems: the styling of our pages has changed (for the worse)

and the navigational links appear twice!

The duplication is happening because the

{% raw %}{% include navigation.html %}{% endraw %} tag is

still present in index.md.

Exercise: Cleaning Up

Remove the include tag for navigation links from all the pages of

your site (e.g. about.md), and set every page to use the

default layout.

Now that we have cleaned the duplicated navigation links, we may want to add another element to our layout. In a similar manner to the navigation links appearing on every page, we may want a common footer to appear too.

Exercise: Expanding the Layout

Expand the layout we have just created to include a footer element at

the bottom defined in _includes/footer.html so that it

appears at the end of each page that uses this layout.

Include the footer file in the _layouts/default.html

layout file as follows:

Remove all references to footer.html from pages as they

will now be included via the layout. Check that this works by reloading

any of the pages that use the default layout. You should

see a footer at the bottom of the page.

HTML Structure, Metadata and a Default Layout

Before we defined a layout for our pages, Jekyll used a default theme to style the site. That default has been overwritten now that we applied a layout file to our site and that means, if we want to use our own customised layouts, we will need to start telling the browser in more detail how we would like our pages to be styled. There is still more to learn about page layouts, so we will come back to this issue of styling at the end of the episode.

You might recall from the

introduction to this tutorial, that a valid HTML page

consists of more than only the content we want to display. We haven’t

written these extra elements (<html>,

<head>, <meta>, etc) in our layout

file: but there are some advantages to defining these yourself: these

invisible elements of a web page describe metadata about the page, which

can be used by Internet search engines to better understand what the

page is about and who it is for. This information is factored in when

the search engine indexes the page, and subsequently makes it more

findable for your target audience. (This is one consideration in the

much larger field of [Search Engine Optimisation][seo-wikipedia].)

For example, to make the browser automatically adjust the way your

pages are shown on different displays/devices, you could include the

metadata element

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">

inside the <head> of your pages. ([Read this

W3Schools page to learn more][w3-viewport].)

It is common practice to define the structural HTML elements of your

site’s pages inside a _layouts/default.html file. This file

defines the bare minimum layout your pages should have.

Exercise: Adding HTML Structural Elements to Default Layout

Modify the default layout file _layouts/default.html

with the following content:

HTML

{% raw %}<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>{{ page.title }}</title>

</head>

<body>

{% include navigation.html %}

<h1>{{ page.title }}</h1>

<section>

{{ content }}

</section>

{% include footer.html %}

</body>

</html>{% endraw %}What do you notice has changed about the pages that use this layout?

After updating the layout, each page includes the page title displayed twice.

Note that we have also included some additional HTML elements in our

default layout - the display of the page title as level-one heading and

wrapping the main page content within <section> and

</section> tags.

We have not been defining the title in the front matter of each of

our pages, and Jekyll is guessing the page title based on the first

heading it finds. The layout displays the page title at the top of the

page, above the page content, which also contains the page title. As a

result, the title ends up being displayed twice. To fix this problem, we

must remove the first-level headings from the Markdown content of our

pages and instead define the title in the page front matter. For

example, about.md should look like this after the

change:

MARKDOWN

---

layout: default

title: About

---

## Project

{{ site.description }}

## Funders

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the XYZ Founding Council, under grant number 'abc'.

## Cite us

You can cite the project as:

> *The Carpentries 2019 Annual Report. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3840372*Layout Inheritance

To prevent the duplication of all this “invisible” HTML across all the layouts we define for a site, Jekyll allows for layouts to be based on other layouts, which can be based on other layouts, and so on. This is referred to as layout inheritance, and is refreshingly easy to use.

For example, let’s say we want to create a slightly different layout

for our home page and include a banner image just below navigation links

to make it pretty. To do so, we first need to upload a banner image to

our repository and create a HTML snippet

_includes/banner.html to include the banner image:

- To add a pre-made banner image, click “Create new file” under the “Add file” dropdown on your repository homepage,

- In the “Name your file…” box, type

images/. The folder name should be automatically inserted in the path displayed next to this box for naming the file. It is good practice to store all image files in a common folder. - You can then leave the file blank and name it

.gitkeep. When you commit the changes, theimagesfolder will have been added to your repository. We will be uploading our banner image to this folder in a moment. Unfortunately GitHub does not provide a way to create a new folder while uploading existing files, only while creating new ones. When making these blank files, which exist only to allow the existence of their parent repository, it is traditional to call them.gitkeep. - Now [download this banner image that we will add to our

pages][banner-image] save it with the name

site_banner.pngand upload the file to your newly-createdimagesfolder on GitHub: you can do this by navigating into the folder and choosing “Upload files” from the “Add file” dropdown you used before.

Now that the banner image is available in our site repository, add

the HTML file _includes/banner.html with the following

content:

Next, we need to create a new layout file

_layouts/home.html and then set it to inherit from the

default layout by adding YAML front matter specifying the

layout (of the layout file) to be default.

We can then add any extentions to the new layout

home.html that will be applied on top of the default

layout. This is what _layouts/home.html file should look

like:

Defining a Layout for a Layout

Note how layouts can be applied not only to regular pages but also to other layouts, effectively making a layout inherit from another layout.

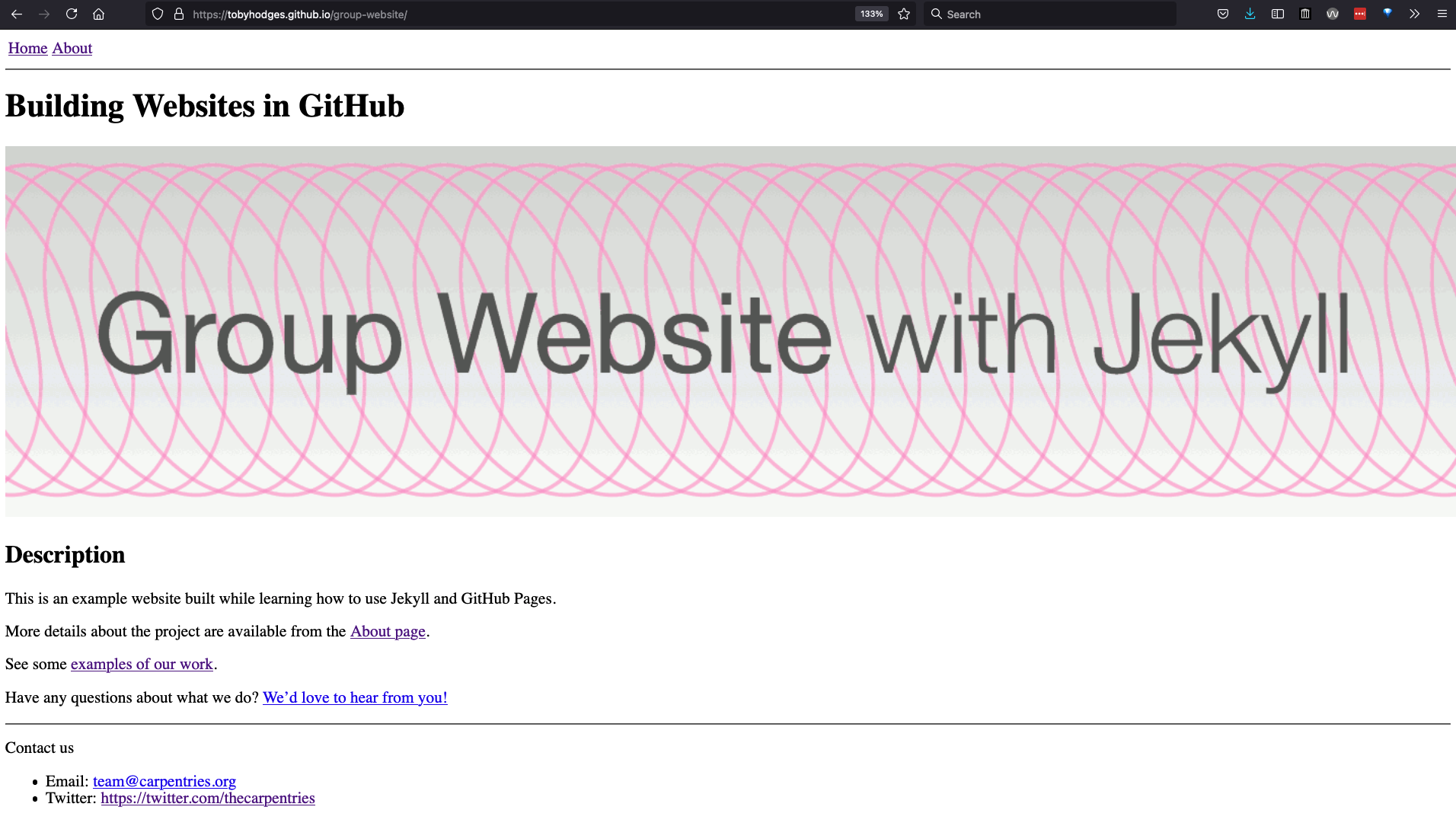

Finally, we can now update the layout of the home page to be

home instead of default by modifying the YAML

front matter. If you reload the home page now, you should now see that

it has all of the structure provided in default layout as

well as the banner image included from the home layout.

The purpose of this approach, defining the core structure that will be common to every page across the site in a default layout, then basing more specific layouts on this foundation, is to keep duplication to a minimum within our repository. Whenever we want to update something about the styling or structure of our site, we should only need to make that change in a single file and let it propagate to all the relevant pages.

We Can’t Include Link References in the Layout

In the previous section, we

recommended that you include a file of references for

the links on your site. Unfortunately, you cannot add this

{% raw %}{% include links.md %}{% endraw %} tag to the

default layout of your site to prevent you from needing to add it at the

bottom of every page. This is a result of [the order of Jekyll’s

rendering process][jekyll-rendering], which constructs the HTML of the

page content in isolation before constructing the HTML of the

relevant layout(s) and nesting it inside. If the link references are

included in the layout rather than the content, those references will

not be available while the content is converted to HTML and the links

will not render correctly. It is annoying to have to remember to add

{% raw %}{% include links.md %}{% endraw %} to the end of

every page’s Markdown, but less annoying than having to manually edit

the same link reference in multiple locations throughout the site.

Using Pre-Existing Layouts From a Theme

We have now seen how to create pages, re-use content across them, and define layouts, and you may be coming to understand that it requires a lot of work to build a website from the ground up. This is not a task we recommend you undertake lightly!

Instead, an alternative is to base your site on one of the many pre-existing themes for Jekyll. Many of these themes are free and open source and, as long as you follow the terms of the license (e.g. remember to give due credit to the original - check the full terms for details), can be adapted/customised to suit your purposes. You can browse a list of Jekyll themes on [jekyllthemes.io][jekyllthemes].

These themes can be elaborate and quite complicated. We hope that the knowledge of Jekyll that you have gained from following this lesson will help you understand how they work and determine what you need to change and where, to make the customisations you need for your site. Reusing pre-existing themes designed by professional web designers helps you focus more on the content of your site, which you can write using more user-friendly and human-readable Markdown.

Key Points

- Files in the

_layouts/directory can be used as page templates - The structure of a page is determined by the

layoutfield in the page front matter - You can find many pre-existing themes for sites on the Internet

- You can avoid duplicated effort by basing new layouts on previous ones

Content from Working With Filters

Last updated on 2022-11-15 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 25 minutes

Writing Blog Posts

Overview

Questions

- How can I control the format of variable values such as dates when I insert them into a page?

Objectives

- Use filters to control the format and content of substituted values.

So far we have been building our site one page at a time, but these individual pages are quite self-contained and their content is likely to be fairly constant: the information on our home page, our contact details etc are unlikely to change very often and, after the site has been built, new pages like this probably won’t be created often. This is good because, if we would like to construct a list or a navigational menu to browse through these pages, it would be annoying to have to expand/reorganise this all the time when a new page is added to the site. (We will actually build an automatically-updating list of pages like this in the final section.)

However, it is common for sites to also host a series of shorter pages as blog posts (usually with a page listing the posts - again, there will be more on this in the final section), which are typically structured differently or contain different information to the standard pages (such as publication date, author name, etc).

To start adding blog posts to our site the first thing we need to do is create a new layout for these posts, inheriting from the default layout we created earlier.

HTML

{% raw %}---

layout: default

---

<strong>Author:</strong> {{ page.author }}

Published on {{ page.date }}

{{ content }}{% endraw %}Save this layout to _layouts/post.html. Now we can

create our first blog post (in the root of our website

repository for now), 1827-11-22-surgeon.md,

remembering to add the author and date fields

to the YAML front matter:

MARKDOWN

{% raw %}---

layout: post

title: I am a Surgeon!

author: Dr James Barry

date: 1827-11-22

---

Today was a good day. I was promoted to Surgeon to the Forces!{% endraw %}You can view the post at

https://GITHUB_USERNAME.github.io/REPOSITORY_NAME/1827-11-22-surgeon.html.

This is a good start! Let’s make a second post before we try to further improve our post layout.

Exercise: Creating Another Post

Write another blog post, in a file called

1851-05-06-DIG.md in the root of our website repository, so

that the rendered page looks like this:

Create the file 1851-05-06-DIG.md in the root of the

repository with the following content:

MARKDOWN

---

layout: post

title: Promoted Again

author: Dr James Barry

date: 1851-05-06

---

Good news: I have been promoted to Deputy Inspector-General of Hospitals.You can view the post at https://GITHUB_USERNAME.github.io/REPOSITORY_NAME/1851-05-06-DIG.html.

Introducing Filters

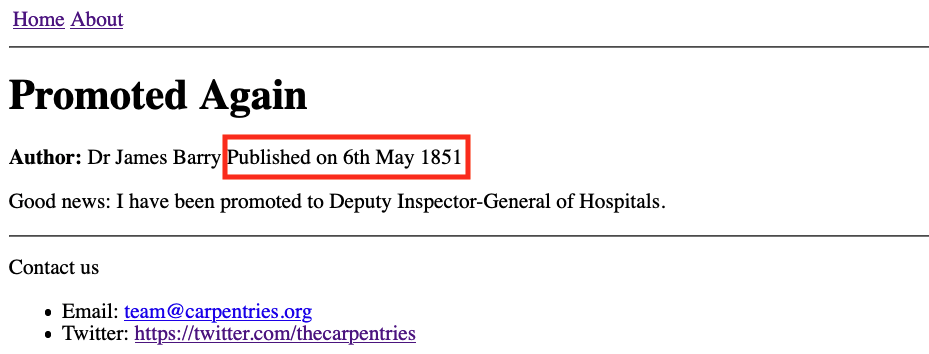

The YYYY-MM-DD format for dates is easy to remember and [great for computers][date-iso] but could be formatted a little more nicely for a human reader.

To ensure consistency throughout all our posts in the future, we can

define the format in which the date should be displayed in the

post.html layout file. The YYYY-MM-DD date in the post

front matter will be converted to a more human format (e.g. “6th May

1851” instead of “1851-05-06” in the second post

1851-05-06-DIG.md we added) at the top of each post, using

a Filter:

Filters like date_to_long_string can be used when

working with variable values on a page. When a filter is applied to a

variable, it processes that value in some way: in the example above, it

converts the format of the date string. We will explore the

"ordinal" part in the exercise below.

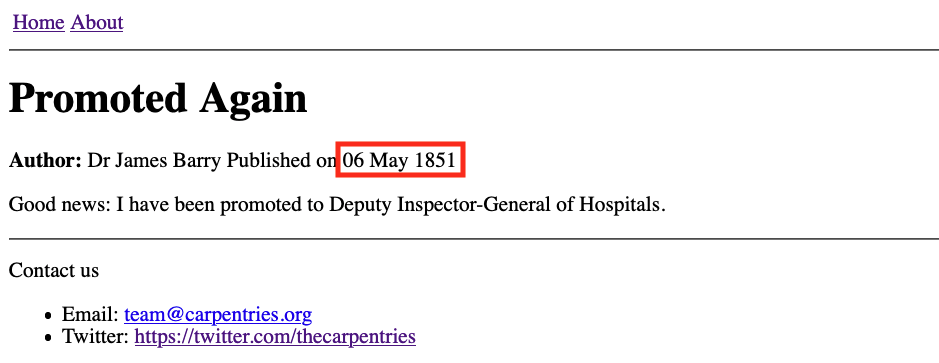

Exercise: Date Formats

"ordinal" is being passed as an argument to the

date_to_long_string filter. To see how this argument is

changing the behaviour of the filter, try removing it in the second post

(1851-05-06-DIG.md), i.e.

{% raw %}{{ page.date | date_to_long_string }}{% endraw %}.

What happens? Which output do you prefer?

Without the ordinal argument,

date_to_long_string produces the output

06 May 1851 (i.e. using the two digits to represent day).