Assessing simple linear regression model fit and assumptions

Last updated on 2024-03-12 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 120 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What does it mean to assess model fit?

- What does \(R^2\) quantify and how is it interpreted?

- What are the six assumptions of simple linear regression?

- How do I check if any of these assumptions are violated?

Objectives

- Explain what is meant by model fit.

- Use the \(R^2\) value as a measure of model fit.

- Describe the assumptions of the simple linear regression model.

- Assess whether the assumptions of the simple linear regression model have been violated.

In this episode we will learn what is meant by model fit, how to interpret the \(R^2\) measure of model fit and how to assess whether our model meets the assumptions of simple linear regression. This episode was inspired by chapter 11 of the book Regression and Other Stories (see here for a pdf copy).

Using residuals to assess model fit

Broadly speaking, when we assess model fit we are checking whether our model fits the data sufficiently well. This process is somewhat subjective, in that the majority of our assessments are performed visually. While there are many ways to assess model fit, we will cover two main components:

- Calculation of the variance in the response variable explained by the model, \(R^2\).

- Assessment of the assumptions of the simple linear regression model.

Both of these components rely on the use of residuals. Recall that our model is characterized by a line, which predicts a value for the outcome variable for each value of the explanatory variable. The difference between an observed outcome and a predicted outcome is a residual. Therefore, our model has as many residuals as the number of observations used in fitting the model.

For a visual example of residuals, see the plot below. A simple

linear regression was fit to Height and Weight

data of participants with an Age of 25. To the right side,

we see a long red vertical line. This is a relatively large residual,

for an individual with a weight greater than predicted by the model. To

the left side, we see a shorter red vertical line. This is a relatively

small residual, for an individual with a weight close to that predicted

by the model.

Measuring model fit using \(R^2\)

A commonly used summary statistic for model fit is \(R^2\), which quantifies the proportion of variation in the outcome variable explained by the explanatory variable. An \(R^2\) close to 1 indicates that the model accounts for most of the variation in the outcome variable. An \(R^2\) close to 0 indicates that most of the variation in the outcome variable is not accounted for by the model.

What does it mean when a model accounts for most of the variation in the outcome variable? Or when it does not? Let’s look at examples of the two extremes: \(R^2=1\) and \(R^2=0\). In these cases, 100% and 0% of the variation in the outcome variable is accounted for by the explanatory variable, respectively.

Below is a plot of hypothetical data, with two regression lines. The blue line goes perfectly through the data points, while the red line is horizontal at the mean of the hypothetical data.

When a model accounts for all of the variation in the outcome variable, the line goes perfectly through the data points. When a model does not account for any of the variation in the outcome variable, the model predicts the mean of the outcome variable, regardless of the explanatory variable.

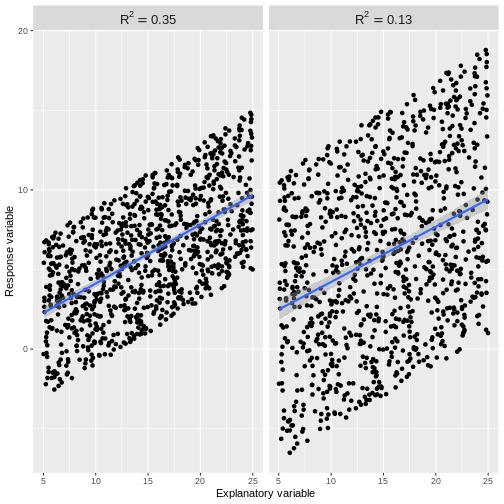

Usually our \(R^2\) value will lie somewhere between these two extremes. An \(R^2\) close to 1 indicates that the data does not scatter much around the model line. Therefore, our model accounts for most of the variation in the outcome variable. An \(R^2\) close to 0 indicates that our model does not predict much better than the mean of the response variable. Therefore, our model does not account for much of the variation in the outcome variable. See for example plots below. The points in the left plot lie closer to the line, so the model explains more of the variation and the \(R^2\) value is higher.

The cut-off for a “good” \(R^2\) value varies by research question and data set. There are scenarios in which explaining 10% of the variation in an outcome variable is “good”, while there are others where we may only be satisfied with much higher \(R^2\) values. The most important thing is to not blindly rely on \(R^2\) as a measure of model fit. While it is a useful assessment, it needs to be interpreted in the context of the research question and the assumptions of the model used.

Exercise

- Find the R-squared value for the

summoutput of ourBPSysAve_AgeMonths_lmmodel from episode 2. - What proportion of variation in average systolic blood pressure is explained by age in our model?

- Does our model account for most of the variation in

BPSysAve?

R

BPSysAve_AgeMonths_lm <- dat %>%

filter(Age > 17) %>%

lm(formula = BPSysAve ~ AgeMonths)

summ(BPSysAve_AgeMonths_lm, confint = TRUE, digits = 3)

OUTPUT

MODEL INFO:

Observations: 3084 (3413 missing obs. deleted)

Dependent Variable: BPSysAve

Type: OLS linear regression

MODEL FIT:

F(1,3082) = 556.405, p = 0.000

R² = 0.153

Adj. R² = 0.153

Standard errors: OLS

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Est. 2.5% 97.5% t val. p

----------------- --------- --------- --------- --------- -------

(Intercept) 101.812 100.166 103.458 121.276 0.000

AgeMonths 0.033 0.030 0.035 23.588 0.000

-----------------------------------------------------------------Since \(R^2 = 0.153\), our model

accounts for approximately 15% of the variation in

BPSysAve. Our model explains 15% of the variation on

BPSysAve, which a model that always predicts the mean would

not.

Assessing the assumptions of simple linear regression

Simple linear regression has six assumptions. We will discuss these below and explore how to check that they are not violated through a series of challenges with applied examples.

1. Validity

The validity assumption states that the model is appropriate for the research question. This may sound obvious, but it is easy to come to unreliable conclusions because of inappropriate model choice. Validity is assessed in three ways:

- Does the outcome variable reflect the phenomenon of

interest? For example, it would not be appropriate to take our

PulsevsPhysActivemodel as representative of the effect of physical activity on general health. - Does the model include all relevant explanatory variables?

For example, we might decide that our model of

TotCholvsBMIrequires inclusion of theSmokeNowvariable. While not discussed in this lesson, inclusion of more than one explanatory variable is covered in the multiple linear regression for public health lesson. - Does the model generalise to our case of interest? For

example, it would not be appropriate to use our

PulsevsPhysActivemodel, which was constructed using people of all ages, if we were specifically interested in the effect of physical activity on pulse rate in those aged 70+. A subsample of the NHANES data may allow us to answer the research question.

Exercise

You are asked to model the effect of age on general health of

South-Americans. A colleague proposes that you fit a simple linear

regression to the NHANES data, using BMI as the outcome

variable and Age as the explanatory variable. Using the

three points above, assess the validity of this model for the research

question.

Exercise(continued)

- There is more to general health than

BMIalone. In this case, we may wish to use a different outcome variable. Alternatively, we could make the research question more specific by specifying that we are studying the effect ofAgeonBMIrather than general health. - Since we are specifically asked to study the effect of

Ageon general health, we may conclude that no further explanatory variables are relevant to the research question. However, there may still be explanatory variables that are important to include, such as income or sex, if the effect ofAgeon general health depends on other explanatory variables. This will be covered in the next lesson. - Since the NHANES data was collected from individuals in the US, this data may not be suitable for a research question relating to individuals in South-America.

2. Representativeness

The representativeness assumption states that the sample is representative of the population to which we are generalising our findings. For example, if we were studying the relationship between physical activity and pulse rate in US adults using the NHANES data, we could assume that our sample is representative of our population of interest. However, if we were to use data from a survey of care homes, our data would not be representative of our population of interest: we would have an overrepresentation of older people, compared to the US adult population.

In combination with the case of interest criterium of the validity assumption, we therefore ask:

- Are the individuals on which our data was collected a subset of the population of individuals which we are interested in studying? This is a component of validity.

- Is our sample of individuals representative of the population of interest in terms of the number of individuals in relevant categories, e.g. ages? This is representativeness.

Note that when the representativeness assumption is violated, this can be solved by including the misrepresented feature as an explanatory variable in the model. For example, if the sample and the population have different age distributions, age can be included as a variable in the model. Linear regression with multiple explanatory variables is covered in the multiple linear regression lesson.

Exercise

One of your colleagues is asked to model the effect of income on dissertation grade in final year undergraduate students. They decide to survey 500 students at your university, asking them for their income and recording their grade upon completion of the thesis.

- Would fitting a model of thesis grade as a function of income using this data violate the case of interest criterium of the validity assumption?

After completing the survey, your colleague finds that the proportion of participants identifying as female in the data is 70%. Presume it is known that at your university, 55% of final year undergraduate students identify as female.

- Would fitting a model of thesis grade as a function of income using this data violate the representativeness assumption?

- Since the sample appears to be a subset of the population of

interest, the case of interest criterium would not be violated.

- Since the sample is not representative of the population of interest, the representativeness assumption would be violated. Including a variable for gender may solve the violation. See the multiple linear regression lesson for details on how to include multiple variables in linear regression.

3. Linearity and additivity

This assumption states that our outcome variable has a linear, additive relationship with the explanatory variables.

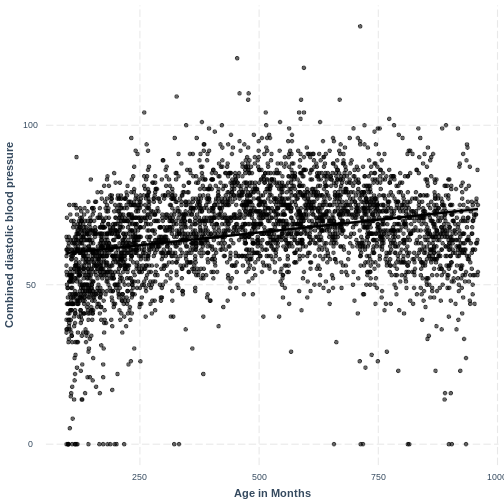

The linearity component means that our outcome variable is

described by a linear function of the explanatory variable(s). On a

practical level, this means that the line produced by our model should

match the shape of the data. We learned to check that the relationship

between our two variables is linear through the exploratory plots. For

an example where the linearity assumption is violated, see the plot

below. The relationship between BPDiaAve and

AgeMonths is non-linear and our model fails to capture this

non-linear relationship.

R

BPDiaAve_AgeMonths_lm <- lm(formula = BPDiaAve ~ AgeMonths, data = dat)

effect_plot(BPDiaAve_AgeMonths_lm, pred = AgeMonths,

plot.points = TRUE, interval = TRUE,

line.colors = "magenta") +

ylab("Combined diastolic blood pressure") +

xlab("Age in Months")

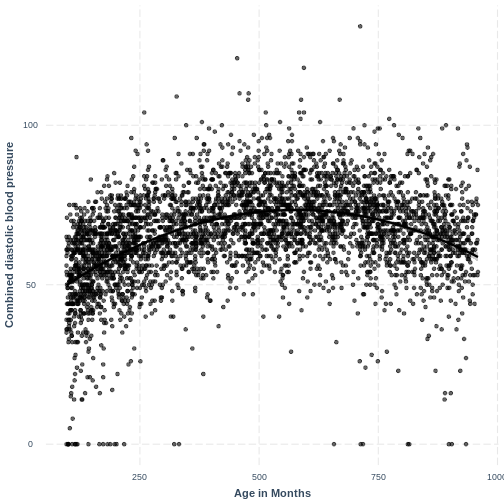

Adding a squared term to our model, designated by

I(AgeMonths^2), allows our model to capture the non-linear

relationship, as the following plot shows. Thus, the model with formula

BPDiaAve ~ AgeMonths + I(AgeMonths^2) does not appear to

violate the linearity assumption.

R

BPDiaAve_AgeMonthsSQ_lm <- lm(formula = BPDiaAve ~ AgeMonths + I(AgeMonths^2), data=dat)

effect_plot(BPDiaAve_AgeMonthsSQ_lm, pred = AgeMonths,

plot.points = TRUE, interval = TRUE,

line.colors = "magenta") +

ylab("Combined diastolic blood pressure") +

xlab("Age in Months")

Exercise

In the example above we saw that squaring an explanatory variable can correct for curvature seen in the outcome variable along the explanatory variable.

In the following example, we will see that taking the log transformation of the dependent variable can also sometimes be an effective solution to non-linearity.

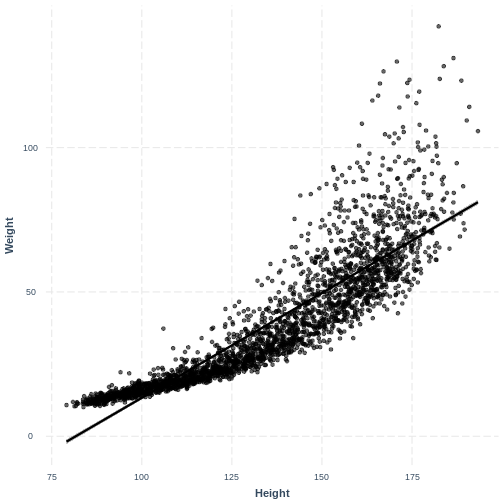

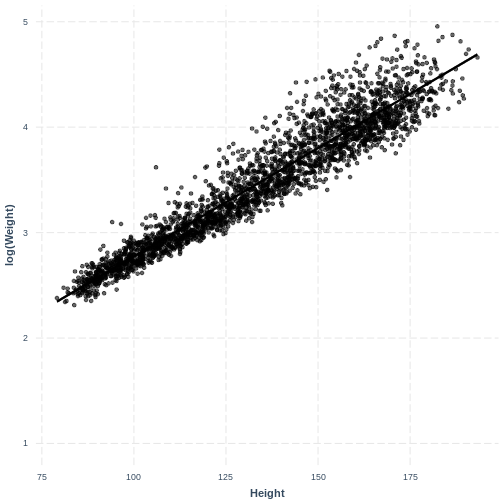

Earlier in this lesson we worked with Weight and

Height in adults. Here, we will work with these variables

in children. Firstly, fit a linear regression model of Weight

(Weight) as a function of Height (Height) in

children (participants below the Age (Age) of 18). Then,

create an effect plot using effect_plot().

R

child_Weight_Height_lm <- dat %>%

filter(Age < 18) %>%

lm(formula = Weight ~ Height)

effect_plot(child_Weight_Height_lm, pred = Height,

plot.points = TRUE, interval = TRUE,

line.colors = "magenta")

Exercise(continued)

There is curvature in the data, which makes a straight line unsuitable.

We will explore the log transformation as a potential solution. Fit a

linear regression model as before, however change Weight in

the lm() command to log(Weight). Then create

an effect_plot. Is the relationship between

log(Weight) and Height different from the

relationship between Weight and Height in

children?

R

child_logWeight_Height_lm <- dat %>%

filter(Age < 18) %>%

lm(formula = log(Weight) ~ Height)

effect_plot(child_logWeight_Height_lm, pred = Height,

plot.points = TRUE, interval = TRUE,

line.colors = "magenta")

The non-linear relationship has now been transformed into a more linear relationship by taking the log transformation of the response variable.

The additivity component means that the effect of any explanatory variable on the outcome variable does not depend on another explanatory variable in the model. When this assumption is violated, it can be mitigated by including an interaction term in the model. We will cover interaction terms in the multiple linear regression for public health lesson.

4. Independent errors

This assumption states that the residuals must be independent of one another. This assumption is violated when observations are not a random sample of the population, i.e. when observations are non-independent. Two common types of non-independence, and their common solutions, are:

- Observations in our data can be grouped. For example, participants in a national health survey can be grouped by their region of residence. Therefore, observations from individuals from the same region will be non-independent. As a result, the residuals will also not be independent.

Common solution: If there are a few levels in our grouping variable (say, less than 6) then we might choose to include the grouping variable as an explanatory variable in our model. If the grouping variable has more levels, we may choose to include the variable as a random effect, a component of mixed effect models (not discussed here).

- Our data contains repeated measurements on the same individuals. For example, we measure individual’s weights four times over the course of a year. Here our data contains four non-independent observations per individual. As a result, the residuals will also not be independent.

Common solution: This can be overcome using random effects, which are a component of mixed effects models (not discussed here).

Exercise

In which of the following scenarios would the independent errors assumption likely be violated?

- We are modeling the effect of a fitness program on people’s fitness

level. Our data consists of weekly fitness measurements on the same

group of individuals.

- We are modeling the effect of dementia prevention treatments on life

expectancy, with each participant coming from one of five care homes.

Our data consists of: life expectancy, whether an individual was on a

dementia prevention treatment and the care home that the individual was

in.

- We are modeling the effect of income on home size in a random sample of the adult UK population.

- Since we have multiple observations per participant, our

observations are not independent. We would hereby violate the

independent errors assumption.

- Our observations are non-independent because multiple individuals

will have belonged to the same carehome. In this case, adding carehome

to our model would allow us to overcome the violation of the independent

errors assumption.

- Since our data is a random sample, we are not violating the independent errors assumption through non-independence in our data.

5. Equal variance of errors (homoscedasticity)

This assumption states that the magnitude of variation in the residuals is not different across the expected values or any explanatory variable. In the context of this assumption, the expected values are referred to as the “fitted values” (i.e. the expected values obtained by fitting the model). Violation of this assumption can result in unreliable estimates of the standard errors of coefficients, which may impact statistical inference. Predictions from the model may become unreliable too. Transformation can sometimes be used to resolve heteroscedasticity. In other cases, weighted least squares can be used (not discussed in this lesson).

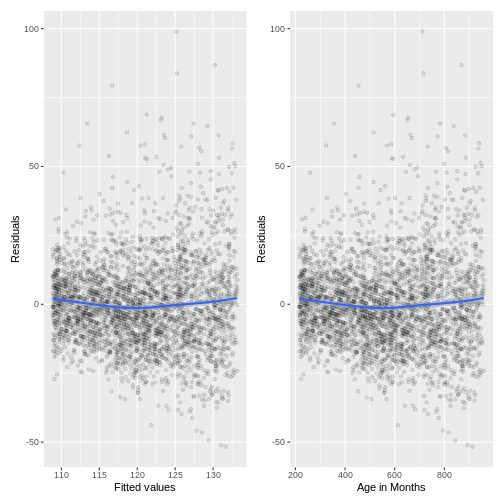

For example, we can study the relationship between the residuals and

the fitted values of our Height_Weight_lm model (the adult

model, fit in episode 2). We store the residuals, fitted values and

explanatory variable in a tibble named residualData. The

residuals are accessed using resid(), the fitted values are

accessed using fitted() and the explanatory variable

(Height) is accessed through the Height column

of Weight_Height_lm$model.

We create a residuals vs. fitted plot named p1 and a

residuals vs. explanatory variable plot named p2. In both

of these plots, we add a line that approximately tracks the mean of the

residuals across the fitted values and explanatory variable using

geom_smooth(). The two plots are brought together into one

plotting region using p1 + p2, where the +

relies on the patchwork package being loaded.

R

Weight_Height_lm <- dat %>%

filter(Age > 17) %>%

lm(formula = Weight ~ Height)

residualData <- tibble(resid = resid(Weight_Height_lm),

fitted = fitted(Weight_Height_lm),

height = Weight_Height_lm$model$Height)

p1 <- ggplot(residualData, aes(x = fitted, y = resid)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.1) +

geom_smooth() +

ylab("Residual") +

xlab("Fitted values")

p2 <- ggplot(residualData, aes(x = height, y = resid)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.1) +

geom_smooth() +

ylab("Residuals") +

xlab("Height")

p1 + p2

Since there is no obvious pattern in the residuals along the fitted values or the explanatory variable, there is no reason to suspect that the equal variance assumption has been violated.

R

BPSysAve_AgeMonths_lm <- dat %>%

filter(Age > 17) %>%

lm(formula = BPSysAve ~ AgeMonths)

residualData <- tibble(resid = resid(BPSysAve_AgeMonths_lm),

fitted = fitted(BPSysAve_AgeMonths_lm),

agemonths = BPSysAve_AgeMonths_lm$model$AgeMonths)

p1 <- ggplot(residualData, aes(x = fitted, y = resid)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.1) +

geom_smooth() +

ylab("Residuals") +

xlab("Fitted values")

p2 <- ggplot(residualData, aes(x = agemonths, y = resid)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.1) +

geom_smooth() +

ylab("Residuals") +

xlab("Age in Months")

p1 + p2

The variation in the residuals does somewhat increase with an

increase in fitted values and an increase in AgeMonths.

Therefore, this model may violate the homoscedasticity assumption.

Because the majority of residuals still lie in the central band, we may

not worry about this violation much. However, if we wanted to resolve

the increase in residuals, we may choose to add more variables to our

model or to apply a Box-Cox transformation on BPSysAve.

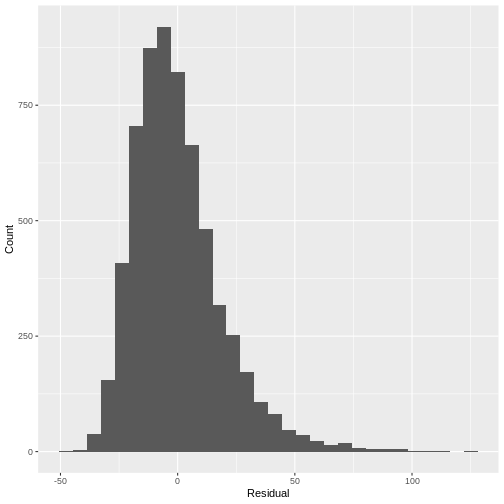

6. Normality of errors

This assumption states that the errors follow a Normal distribution. When this assumption is strongly violated, predictions of individual data points from the model are less reliable. Small deviations from normality may pose less of an issue. One way to check this assumption is to plot a histogram of the residuals and to ask whether it looks strongly non-normal (e.g. bimodal or uniform).

For example, looking at a histogram of the residuals of our

Height_Weight_lm model reveals a distribution that is

slightly skewed. Since this is not a strong deviation from normality, we

do not have to worry about violating the assumption.

Note that if a model includes a grouping variable (e.g. a two-level categorical variable), the normality of the residuals is to be checked separately for each group. Also note that in the previous episode, we only covered prediction of the mean, not of individual data points. A deviation of the residuals from normality is usually not a concern for predictions of the mean.

R

residuals <- tibble(resid = resid(Weight_Height_lm))

ggplot(residuals, aes(x=resid)) +

geom_histogram() +

ylab("Count") +

xlab("Residual")

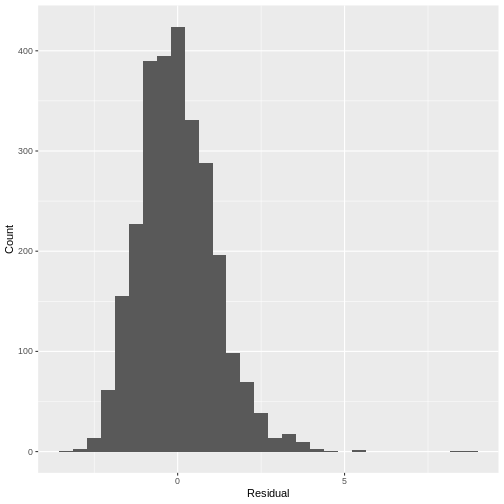

R

TotChol_SmokeNow_lm <- lm(formula = TotChol ~ SmokeNow, data = dat)

residuals <- tibble(resid = resid(TotChol_SmokeNow_lm))

ggplot(residuals, aes(x=resid)) +

geom_histogram() +

ylab("Count") +

xlab("Residual")

Since the distribution is only slightly skewed, we do not have to worry about violating the normality assumption.

Key Points

- Assessing model fit is the process of visually checking whether the model fits the data sufficiently well.

- \(R^2\) quantifies the proportion of variation in the response variable explained by the explanatory variable. An \(R^2\) close to 1 indicates that most variation is accounted for by the model, while an \(R^2\) close to 0 indicates that the model does not perform much better than predicting the mean of the response.

- The six assumptions of the simple linear regression model are validity, representativeness, linearity and additivity, independence of errors, homoscedasticity of the residuals and normality of the residuals.

- We can check the assumptions of a simple linear regression model by carefully considering our research question, the data set that we are using and by visualising our model parameters.