Linear regression with one continuous explanatory variable

Last updated on 2024-03-12 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 40 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can we assess whether simple linear regression is a suitable way to model the relationship between two continuous variables?

- How can we fit a simple linear regression model with one continuous explanatory variable in R?

- How can the parameters of this model be interpreted in R?

- How can this model be visualised in R?

Objectives

- Use the ggplot2 package to explore the relationship between two continuous variables.

- Use the lm command to fit a simple linear regression with one continuous explanatory variable.

- Use the jtools package to interpret the model output.

- Use the jtools and ggplot2 packages to visualise the resulting model.

In this episode we will study linear regression with one continuous

explanatory variable. As explained in the previous episode, the

explanatory variable is required to have a linear relationship with the

outcome variable. We can explore the relationship between two variables

ahead of fitting a model using the ggplot2 package.

Exploring the relationship between two continuous variables

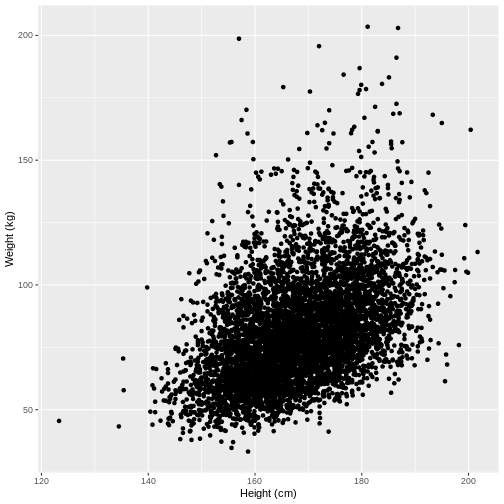

Let us take Weight and Height of adults as

an example. In the code below, we select adult participants with the

command filter(Age > 17). We then initiate a plotting

object using ggplot(). The data is passed on to

ggplot() using the pipe. We then select the variables of

interest inside aes(). In the next line we create a

scatterplot using geom_point(). Finally, we modify the x

and y axis labels using xlab() and ylab().

Note that the warning message “Removed 320 rows containing missing

values (geom_point)” means that there are participants without recorded

height and/or weight data.

R

dat %>%

filter(Age > 17) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Height, y = Weight)) +

geom_point() +

xlab("Height (cm)") +

ylab("Weight (kg)")

WARNING

Warning: Removed 320 rows containing missing values (`geom_point()`).

Exercise

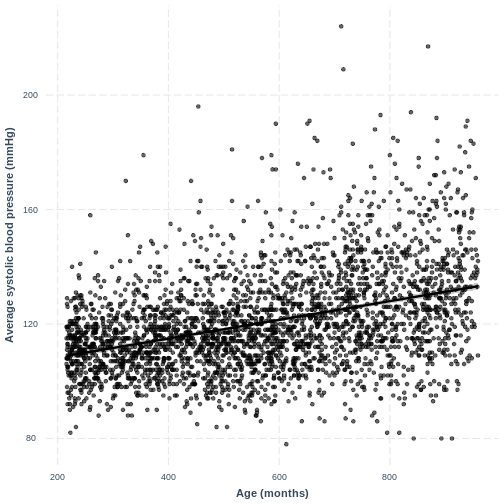

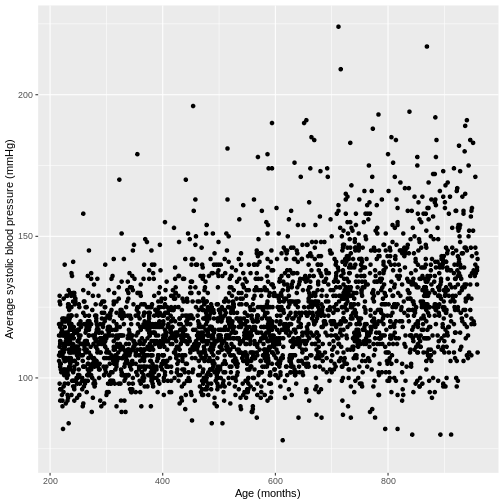

You have been asked to model the relationship between average systolic blood pressure and age in adults in the NHANES data. In order to fit a simple linear regression model, you first need to confirm that the relationship between these variables appears linear. Use the ggplot2 package to create a plot, ensuring that it includes the following elements:

- Average systolic blood pressure (

BPSysAve) on the y-axis and age (AgeMonths) on the x-axis, from the NHANES data, only including data from individuals over the age of 17. - These data are presented using a scatterplot.

- The y-axis labelled as “Average systolic blood pressure (mmHg)” and the x-axis labelled as “Age (months)”.

R

dat %>%

filter(Age > 17) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = AgeMonths, y = BPSysAve)) +

geom_point() +

ylab("Average systolic blood pressure (mmHg)") +

xlab("Age (months)")

Fitting and interpreting a simple linear regression model with one continuous explanatory variable

Since there is no abnormal shape to the scatterplot (e.g. curvature

or multiple clusters), we can proceed with fitting our linear regression

model. First, we subset our data using filter(). We then

fit the simple linear regression model with the lm()

command. Within the command, the model is denoted by

formula = outcome variable ~ explanatory variable.

R

Weight_Height_lm <- dat %>%

filter(Age > 17) %>%

lm(formula = Weight ~ Height)

We will interpret our results using a summary table and a plot. The

summary table can be obtained using the summ() function

from the jtools package. We provide the function with the

name of our model (Weight_Height_lm). We can also specify

that we want confidence intervals for our parameter estimates using

confint = TRUE. Finally, we specify that we want estimates

with three digits after the decimal point with

digits = 3.

We will come to interpreting the Model Fit section in a

later episode. For now, take a look at the parameter estimates at the

bottom of the output. We see that the intercept (i.e. \(\beta_0\)) is estimated at -70.194 and the

effect of Height (i.e. \(\beta_1\)) is estimated at 0.901. The model

therefore predicts an average increase in Weight of 0.901

kg for every 1 cm increase in Height.

R

summ(Weight_Height_lm, confint = TRUE, digits = 3)

OUTPUT

MODEL INFO:

Observations: 6177 (320 missing obs. deleted)

Dependent Variable: Weight

Type: OLS linear regression

MODEL FIT:

F(1,6175) = 1398.215, p = 0.000

R² = 0.185

Adj. R² = 0.184

Standard errors: OLS

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Est. 2.5% 97.5% t val. p

----------------- --------- --------- --------- --------- -------

(Intercept) -70.194 -78.152 -62.237 -17.293 0.000

Height 0.901 0.853 0.948 37.393 0.000

-----------------------------------------------------------------We can therefore write the formula as:

\[E(\\text{Weight}) = -70.19 + 0.901 \\times \\text{Height}\]

Interpretation of the 95% CI and p-value ofHeight

If prior to fitting our model we were interested in testing

the hypotheses \(H_0: \beta_1 = 0\) vs

\(H_1: \beta_1 \neq 0\), we could check

the 95% CI for Height. Recall that 95% of 95% CIs are

expected to contain the true population mean. Since this 95% CI does not

contain 0, we would be fairly confident in rejecting \(H_0\) in favour of \(H_1\). Alternatively, since the p-value is

less than 0.05, we could reject \(H_0\)

on those grounds.

Note that the summ() output below shows

p = 0.000. P values are never truly zero. The

interpretation of p = 0.000 is therefore that

p < 0.001, as the p-value was rounded to three

digits.

Often the null hypothesis tested by summ(), \(H_0: \beta_1 = 0\), is not very

interesting, as it is rare that we expect a variable to have an effect

of 0. Therefore, it is usually not necessary to pay great attention to

the p-value. On the other hand, the 95% CI can still be useful, as it

provides an estimate of the uncertainty around our estimate for

\(\beta_1\). The narrower the 95% CI,

the more certain we are that our estimate for \(\beta_1\) is close to the population mean

for \(\beta_1\).

Exercise

Now that you have confirmed that the relationship between

BPSysAve and AgeMonths does not appear to

deviate from linearity in the NHANES data, you can proceed to fitting a

simple linear regression model.

- Using the

lm()command, fit a simple linear regression of average systolic blood pressure (BPSysAve) as a function of age in months (AgeMonths) in adults. Name thislmobjectBPSysAve_AgeMonths_lm. - Using the

summfunction from thejtoolspackage, answer the following questions:

- What average systolic blood pressure does the model predict, on

average, for an individual with an age of 0 months?

- By how much is average systolic blood pressure expected to change,

on average, for a one-unit increase in age?

- Given these two values and the names of the response and explanatory variables, how can the general equation \(E(y) = \beta_0 + {\beta}_1 \times x_1\) be adapted to represent your model?

R

BPSysAve_AgeMonths_lm <- dat %>%

filter(Age > 17) %>%

lm(formula = BPSysAve ~ AgeMonths)

summ(BPSysAve_AgeMonths_lm, confint = TRUE, digits=3)

OUTPUT

MODEL INFO:

Observations: 3084 (3413 missing obs. deleted)

Dependent Variable: BPSysAve

Type: OLS linear regression

MODEL FIT:

F(1,3082) = 556.405, p = 0.000

R² = 0.153

Adj. R² = 0.153

Standard errors: OLS

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Est. 2.5% 97.5% t val. p

----------------- --------- --------- --------- --------- -------

(Intercept) 101.812 100.166 103.458 121.276 0.000

AgeMonths 0.033 0.030 0.035 23.588 0.000

------------------------------------------------------------------ 101.8 mmHg.

- Increase by 0.033 mmHg/month.

- \(E(\text{Average systolic blood pressure}) = 101.8 + 0.033 \times \text{Age in Months}\).

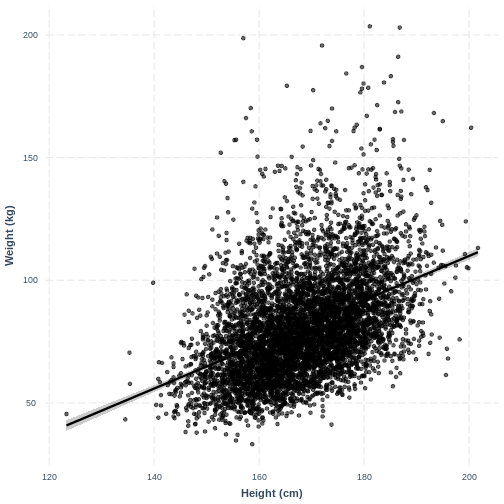

Visualising a simple linear regression model with one continuous explanatory variable

We can also interpret the model using a line overlayed onto the

previous scatterplot. We can obtain such a plot using

effect_plot() from the jtools package. We

provide the name of our model, followed by a specification of the

explanatory variable of interest with pred = Height. Our

current model has one explanatory variable, but in later lessons we will

work with multiple explanatory variables so this option will be more

useful. We also include a confidence interval around our line using

interval = TRUE and include the original data using

plot.points = TRUE. Finally, we specify a red colour for

our line using colors = "red". As before, we can edit the x

and y axis labels.

R

effect_plot(Weight_Height_lm, pred = Height, plot.points = TRUE,

interval = TRUE, line.colors = "magenta") +

xlab("Height (cm)") +

ylab("Weight (kg)")

Exercise

You have been asked to report on your simple linear regression model, examining systolic blood pressure and age, at the next lab meeting. To help your colleagues interpret the model, you decide to produce a figure. Make this figure using the jtools package. Ensure that the x and y axes are correctly labelled.

R

effect_plot(BPSysAve_AgeMonths_lm, pred = AgeMonths, plot.points = TRUE,

interval = TRUE, line.colors = "magenta") +

xlab("Age (months)") +

ylab("Average systolic blood pressure (mmHg)")